We use the names almost every day and they seem so commonplace that modern-day travelers don’t think much about them. But every name of a place has a story to tell, as does the person who did the naming.

Much of the local site names around Tacoma come from a single person, Lt. Charles Wilkes. He was the first formal American explorer of the area that we now call Puget Sound. The mapping of Puget Sound was part of a larger American effort that started in 1938 to chart Antarctica and sail around the world. Six ships started the effort but only two returned to Virginia in 1842, having logged 87,000 miles and marking the last all-sail ship to circle the globe.

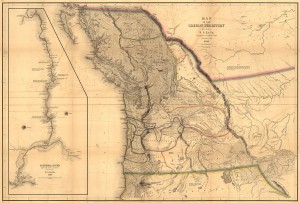

His expedition of Puget Sound, on the U.S. Navy ships Vincennes and Porpoise during the summer of 1841, involved the charting and naming of islands and inlets along the waterway that remain to this day.

Wilkes arrived in present-day DuPont in May of 1841 to set up an observatory on the bluff of Sequalitchew Creek, near what was then the Hudson’s Bay Co. trading post of Fort Nisqually. That work done, the exploration began in the aptly named Commencement Bay that is now Tacoma’s picturesque waterway. Point Defiance was so duly named because it seemed a natural location to guard the bay from attack. A passage from the period reads, “It seems as if intended by nature to afford every means of defense to Puget’s Sound, the only entrance to which is through the Narrows, which if strongly fortified, would bid defiance to any attack and guard its entrance against any force.”

During the sailing around Puget Sound, which was named by George Vancouver in honor of Peter Puget decades before, Wilkes named the sights he spotted through his spyglass, giving his crew and those he met along the way immortality of sorts by borrowing their names for the locations. Among the list are: McNeil island after and William Henry McNeill — with two l’s — who was captain of the Hudson Bay Co’s steamship, Beaver; Fox Island was named for J. L. Fox, a ship’s surgeon; while a less significant land mass, Days Island was named after Fox’s hospital steward, Stephen W. Days; and Anderson Island was named after Fort Nisqually’s Alexander C. Anderson.

Even the name Narrows has its roots to Wilkes, who named the span as the dividing line between Puget Sound and Admiralty Inlet.

But not all of Wilkes’ naming survived the passage of time. His Brackenridge Passage between Fox and McNeil islands now has the name Bruce Channel, and Tacoma’s Browns Point was renamed after the longtime lighthouse keeper Oscar Brown. Wilkes had named it Point Harris.

What is possibly more interesting about Wilkes outside of his naming of the local area is his standing in literary history. See, he was a bit of a jerk when it came to leading his crew. He was a bit “lash happy” when it came to disciplining the sailors under his command, something that would immortalize him more than his expedition to Puget Sound.

Upon his return to the East Coast, word of Wilkes’ harsh discipline and personal arrogance inspired Herman Melville’s “Moby Dick” character, Captain Ahab. Wilkes was eventually charged with excessive abuse but was later found not guilty.

Despite being found not guilty, Wilkes’ career never fully recovered, especially after he blasted the Secretary of the Navy for not promoting him, a tirade that led to an eventual court martial. He died as a Rear Admiral on February 8, 1877. His remains are buried at Arlington National Cemetery, under a marker that says, “he discovered the Antarctic continent.”