The phrase “midnight in broad daylight” was used by poet Sankichi Toke to describe the moment America’s first atomic bomb explosively turned light to dark in Hiroshima, Japan, at 8:15 a.m. August 6, 1945.

Midnight in Broad Daylight is also the title of an elegantly written and sensitively told true story of the Japanese-American Fukahara family. Trapped between the conflicting currents of two cultures, the Fukahara family’s struggle is set against the backdrop of the ferocious combat of World War II.

However, it is not just a story of war or culture. It is about how lives can so quickly transform from lightness to dark, says historian and author Pamela Rotner Sakamoto, Ph.D.

Sakamoto tells the compelling tale from the perspective of the everyday people, not the ones in power, who experienced the reality of the time and day-to-day consequences of decisions made by those at the top.

“I really wanted it to be a human story,” Sakamoto said.

The author will speak at Saint Martin’s University on April 27 at 7:00 p.m. about the book, sharing her experience with the family and crafting their personal story. Earlier the same day, Sakamoto will engage with those who have read Midnight in Broad Daylight at Lacey Timberland Library, discussing the book, answering reader questions in a book club-style event.

The beautifully crafted prose of Sakamoto pulls the reader in, painting an honest but non-judgmental picture of the family and its history.

The family story includes brutal exclusion, internment (“incarceration,” Sakamoto calls it), the horror of a ruthless, military-run Japan and the real possibility of brother fighting brother as their loyalties, and locations, divide them. The tale’s tragedy culminates in their Japanese home city becoming the target of the most horrible weapon ever created.

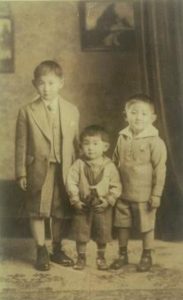

The Fukuhara children – Harry, Frank, Victor, Pierce and Mary – were raised in Auburn, Washington, by their parents and were considered “American born, biculturally bred.”

Kinu, their mother, was a “picture bride.” In 1911, she travelled to Seattle for an arranged marriage after only an exchange of pictures between the two families.

In 1926, the family relocated to Auburn. The parents were “Isei” (ee-say), first-generation Americans while the children were “Nisei” (knee-say), second generation.

The story shares the discrimination common against Japanese immigrants at the time and challenges it posed for the family.

“Once (Japanese immigrants) started to succeed, they (the government) shut it down,” Sakamoto said of rights for the Japanese. “It is a thread running through the history of America and its immigrants.”

During the depression, their father died and the children moved with their mother back across the Pacific to the family home in Hiroshima despite never having visited Japan.

On December 7, 1941, the day Pearl Harbor was attacked, Harry and Mary were living in the United States while their mother and three brothers were still in Japan.

It is with the official start of the war that the real horrors began for the Fukahara family. Harry, Mary and her young child were sent to an internment camp in Arizona. The remainder of the family, still in Japan, endured life under an increasingly militaristic Japan, struggling to survive day-to-day.

Throughout their early lives, but especially during the war, the nisei “juggled two cultures,” their loyalties in both countries suspect. “I wanted to tell the story of the two cultures,” Sakamoto says.

Fluent in Japanese and English, Harry volunteered in the U.S. Army to interpret documents and interrogate prisoners. It was a struggle to be a Japanese-American soldier and every time he changed Army units, he needed a bodyguard to protect him from “friendly fire.”

Frank, the youngest, endured brutal military training in high school, yet wasn’t drafted until 1945. Victor, the elder son, joined the Army in 1938, later transitioning to work in a factory in Hiroshima. Pierce eventually ended up in the Army as well, but was sickly and never engaged in combat.

As a US soldier, Harry was landing on beaches with his Army brothers yet knew he might face his biological brothers any day. He was scheduled to storm mainland Japan in the first wave.

“How do you fight your own brothers?” Sakamoto says. A comparison could be made to the American Civil war, she said, especially because the siblings “were all Americans.”

Sakamoto shares Harry’s perspective on the Japanese military mentality: “The enemy didn’t fight to live. They fought to die.” Unfortunately, Frank was included in this, forced into training to be a “tokkotai”, a special attack forces soldier preparing to die. “We decided to die to the last man,” Frank told Sakamoto.

The ground conflicts, however, never occurred as the US dropped the bomb on Hiroshima. Sakamoto doesn’t gloss over the horrifying effects of the weapon.

On the 75th anniversary of the Japanese internment, some in the World War II generation might remain bitter and condemnatory – saying the Japanese deserved it. However, a Japanese Times review called the book a “powerful plea for empathy.”

To illustrate the impact of the book, Sakamoto shares this e-mail she received: “Your book has helped me resolve the prejudices that were so carefully hidden away by the WWII generation. At 60 years of age, I realized that I was raised to hate the Japanese.”

The book and the April 27 event, a collaboration between the Saint Martin’s University O‘Grady Library and the Lacey Timberland Library, has impact for any generation. Kelsey Smith, senior adult services librarian at Timberland’s Lacey branch said the personal nature of the story is appealing. “I’m really interested in stories about people,” she said, noting the history of an era illustrated through the story of a family.

The 75th anniversary of Japanese internment and the fact that “this is an interesting cultural moment when talking about immigrants” led to the project, said Kael Moffat, information literacy chairman at the University.

Meet Pamela Rotner Sakamoto, Ph.D. on April 27 and engage in a book club style discussion about Midnight in Broad Daylight from 2 p.m. to 3 p.m. at the Lacey Timberland Library. From 7:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m., Sakamoto will speak at the St. Martin’s University Norman Worthington Conference Center. Sakamoto will be available to sign books after the program. Both events are free and open to the public. For more information call 360-491-3860.

Sponsored