Tacoma was a rough and tumble town during the turn of the last century. It was only a few years old after all, so some growing pains should probably have been expected. At least one wasn’t, and it set the city on a short-lived panic.

The day was July 2, 1896, when representatives of the Tacoma firefighters walked into City Hall with a simple demand: They wanted their back pay and money to feed the horses that pulled their water-pumping equipment. They wanted city officials to pay up or firefighters would simply not respond to fire calls starting the following morning.

City Hall and the community at large was abuzz within hours, especially because the town’s homes and shops were almost exclusively made from wood. To understand the panic, one must first understand what Tacoma was 120 years ago.

The Washington Territorial Legislature had only just authorized the merger of Tacoma City and New Tacoma 12 years prior to the “strike.” Tacoma was a new city. The famous Thea “Tug Boat Annie” Foss was in the early stages of what would become the largest tug company on the West Coast. Tacoma had just completed the construction of what is now Old City Hall. And heck, firefighters had only started being paid from city coffers for six years.

Up until 1890, the seemingly everyday fire calls caused by a fallen oil lamp or other Wild West mishaps were answered by volunteer firefighters or firemen’s clubs that often had to hand-build their own equipment and sew their own uniforms. But that started to change after Seattle suffered a fire so large that Tacoma volunteers also responded to the general call for assistance. The Great Seattle Fire of 1889 leveled 25 blocks of downtown in a matter of hours.

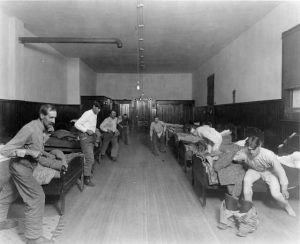

Tacoma didn’t want a similar tragedy. City leaders formed a salaried fire department and bought relatively modern equipment: a Silsby steam fire engine, American Fire Apparatus hose wagon, two sliding poles, six rubber coats, four horse blankets and a crowbar. The inventory of equipment bought that year, 1890, also included six spittoons, $336.10 worth of oats, and $8.05 worth of carrots for the horses, according to “100 Years of Firefighting in the City of Destiny.”

But troubles flared up soon after the department formed since the city coffers couldn’t keep up with expenses of operating a growing city. Firefighters and other city employees were often paid in credits during lean times and weren’t paid at all when budgets outstretched city wallets.

Tacoma firefighters were fed up by the time they threatened to strike. They had not been paid at all for the month of June 1896 and were even having to buy food for the department’s 33 horses out of their own pockets just to answer fire calls in honest of being paid for their services by payday at the end of the month.

A threat of a firemen’s strike in an all-wood city was a big deal, but Mayor Angelo Fawcett thought firefighters were bluffing and did little at the beginning to find enough money in the city treasury to pay them and feed the horses, an amount of about $3,000. The city simply didn’t have the money, after all.

However, as the clock ticked away precious minutes, Tacoma’s business leaders stepped in to form an emergency fund drive. W. H. Woodruff, manager of the Peoples Store, was appointed chairman of the fundraising committee with Calvin Philips serving as secretary. They were well aware of what would happen if word got out about Tacoma not having a fire department. Insurance companies would simply cancel policies as a way to safeguard against large payouts if a fire leveled the city. Lack of insurance would worry investors and could cause a panic.

Woodruff himself started the fund with $300. By the end of the meeting, the committee had raised $1,000. It was a large amount of money for the day, but it was not enough and many businesses in Tacoma were either already cash-strapped or simply closed for the day.

The committee members went door to door well into the night. By the morning, they had raised $2,780.

They went to the firemen knowing full well they were $600 short and hoped the would-be strikers would accept their effort and stay on the job. They did. The money was proportioned out to the men and the horses were fed.

It was a good thing that firefighters stayed at work because it served as an impetus of tighter controls over the city’s cash flow. Tacoma was certainly grateful when fire broke out at the Tacoma’s Western Washington Industrial Exposition building in 1898. The building was the largest wood-frame building on the West Coast and stretched from Tacoma Avenue to North 8th Street. It burned to the ground, but the flames could have easily spread throughout the city had firefighters not answered the emergency call.