The reasons why Tacoma isn’t bigger than Seattle are complex, as most historical issues tend to be since the nuances fuel historical debates to this day. Like everything, it had to do with money.

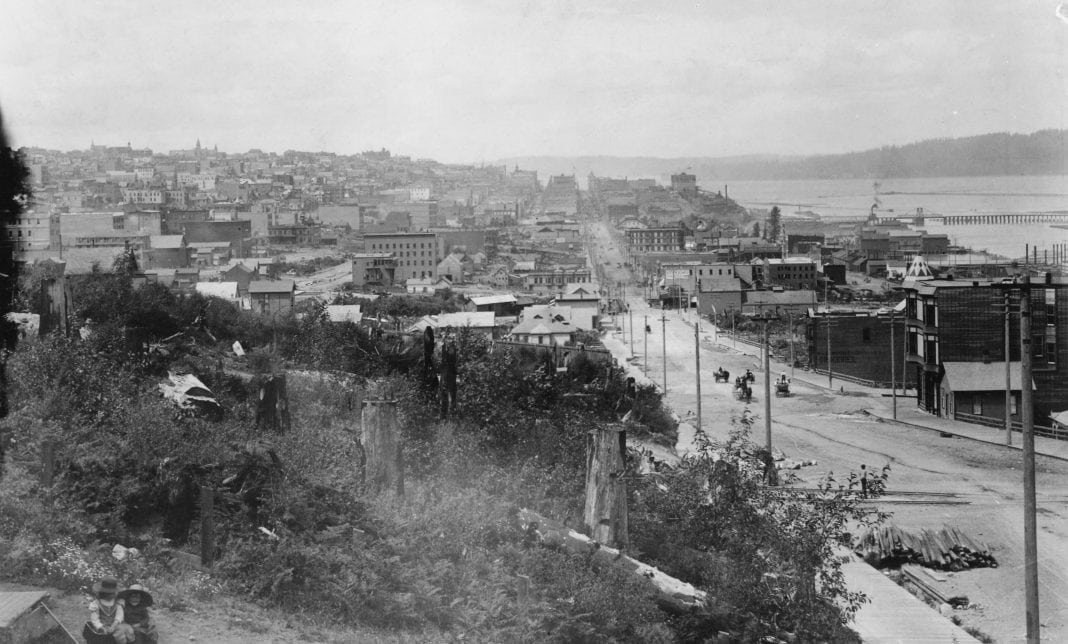

![]() Flashback to the 1880s for a minute. The Puget Sound region was the Wild West, with massive swaths of open land dotted by settlements, trading posts and timber towns. Tacoma had just 1,098 residents in 1880, while Seattle had 3,533. But Tacoma’s star was on the raise, while Seattle’s was showing signs of burn out.

Flashback to the 1880s for a minute. The Puget Sound region was the Wild West, with massive swaths of open land dotted by settlements, trading posts and timber towns. Tacoma had just 1,098 residents in 1880, while Seattle had 3,533. But Tacoma’s star was on the raise, while Seattle’s was showing signs of burn out.

Tacoma had won the first round in its battle with Seattle in 1873 by being named the Western terminus of the Northern Pacific Railroad and quickly boomed while Seattle struggled. The rails in Tacoma allowed merchant ships to offload their cargo in Commencement Bay and send their goods by train cars bound for Chicago, New York and other markets to the east while also enabling Midwest grains, goods and people to flow in the opposite direction.

East Coast companies set up shop in Tacoma to tap into the growing economy of the Pacific Northwest and communicate about their profits back via the telegraph office that came with the railroad tracks. Land was cheap and money was made. It was good to be a Tacoman. People flooded into the area where jobs were bountiful and opportunities waited at every corner.

“It was the fastest growing city in the West,” former Tacoma Mayor and local guru of all things Tacoma history Bill Baarsma said. “(Rudyard) Kipling called it the boomiest of boomtowns.”

Tacoma had a population of 36,006 by 1890, a boom of 3,179.2 percent in just 10 years. But not to be outdone, Seattle had formed its own rail service, the Seattle & Walla Walla Railroad, to feed off the profitable railroad-borne commerce. It too had boomed. Its population in 1890 was 42,837, a respectable 1,112.5 percent growth rate during the same period, even with the Great Seattle fire of 1889.

Tacoma’s population was estimated to be 56,000 in 1893, the year Seattle finally landed its transcontinental railroad connection with the Great Northern Railway. But still, Tacoma was ballooning faster. That fact made the bubble burst even louder.

The burst came with the Panic of 1893. The global depression had started in Argentina over ill-conceived commodity trading and a failed insurrection that left the world’s monied class over extended and in search of more secure ways to hold onto their wealth. They sought gold by the ton. Banks ran out. Panic started.

“This was a national panic,” Baarsma said. “It was huge.”

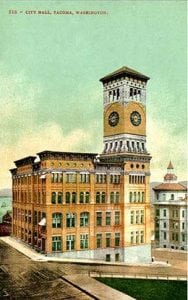

Tacoma’s close ties to East Coast money came back to almost doom the city. Investors and companies pulled back their dollars to protect their Atlantic-based interests at the cost of projects and ventures in the City of Destiny. Banks closed by the dozens. Savings accounts vanished overnight. Businesses shuttered their doors without paying any final wages to their workers. And it couldn’t have happened at a worse time for Tacoma. The city had just spent thousands of dollars building its majestic City Hall and spent another $1.75 million to buy the Tacoma Light and Water Co. from Charles Wright.

Tacoma developer Allen C. Mason went from being a multimillionaire to penniless in a matter of months by buying back all the houses his customers could no longer afford. He lost his 36-room mansion in the process. He had to sell it to Whitworth College, which it used as its hub until moving to Spokane in 1913.

Money was so tight that people started making their own or bartering for food. Tacomans lived off what they could catch, hunt or harvest from the waterways. Many just simply left town. The city’s population dropped by 20,000 people.

“People just left to find other opportunities,” Baarsma said.

Noted Northwest historian Murray Morgan dedicated a whole chapter of his book, “Puget’s Sound: A Narrative of Early Tacoma and the Southern Sound” on the topic of the hardship of fortunes won and lost during the panic that almost killed the city.

The depression lingered until 1897. Tacoma lumbered forward, while Seattle rocketed ahead courtesy of the Alaskan Gold Rush that started in July of that year when the first of the gold prospectors arrived with more than $1 million of gold. That triggered a flood of some 100,000 gold seekers sailing to the Klondike, a majority buying their supplies in Seattle before boarding ships bound for Alaska.

Tacoma just couldn’t catch up after that. It had a population of 37,714 in 1900, while Seattle had 80,671 and then 237,194 in 1910. Tacoma had just 83,743 by then. Seattle had won.