You know the scene. A detective slumps behind his desk. He pulls yet another cigarette from his rumpled suit and swigs booze from a dirty glass. A buxom blonde with legs longer than a discount flight to Cleveland needs his help. He takes the case.

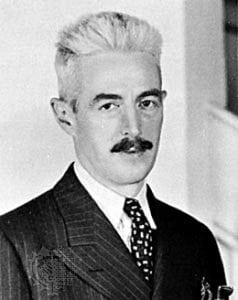

The vision is a cliché these days. But the well-worn scene revolutionized American literature when Dashiell Hammett invented it.

And he did it with Tacoma on his mind.

Hammett is considered the father of the hard-boiled detective genre, also known as crime noir, that is exemplified by his most celebrated novel, “The Maltese Falcon.” It became a movie in 1941, starring Humphrey Bogart as the iconic Sam Spade. Hammett crafted the whole crime world that would make him famous by marrying his “just the facts” training as an investigator with the Pinkerton National Detective Agency to the colorful characters and crimes he saw in Tacoma. His union of realism and gritty details diverged from the “white hat” novels of the dime-store era to birth a crime genre with deep descriptions of drunk detectives wearing fedoras and sweat-stained shirts meeting tight-dressed femme fatales in some fleabag office that could easily wash away in the rain-soaked streets of a city filled with crime, vice, corruption and double dealings.

“Everyone gives credit to Hammett for really getting into it,” Tacoma historian Michael Sullivan said, noting Hammett’s creation of dark settings and tragically flawed anti-heroes. “That is what Hammett is playing with. He is dealing with people who are broken. Hammett was dealing with all of that, and he was dealing with that in Tacoma.”

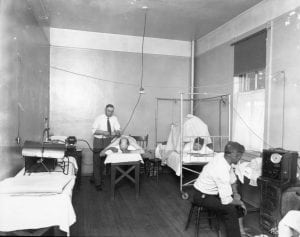

Hammett came to Tacoma in the fall of 1920 to get treatment alongside other “lungers” and shell-shocked vets at Cushman Hospital. He had gotten tuberculosis during the Great War and it had flared up with its signature bouts of bloody coughs while he investigated the unionizing efforts of workers at a copper mine in Montana the previous year. He stepped off the train at Union Station to find a city torn by vice, violence and corruption at all levels of the City of Destiny. It was a true Gritty City, where rival newspapers tried to out sensationalize each other with vivid details of grizzly crime scenes that often only came after greenbacks crossed the palm of someone at City Hall. It was a city where everyone was on the take, and people flowed into basement speakeasies to choke down shots of booze without much care of being arrested. The well-paid vice squads stayed bought and knew not to go against the deal. Headlines screamed the violence of the day, “Masked Bandit Slain in Gun Duel at Pool Hall,” “3 Tacomans shot by gunman; 2 may die,” and “Tacoma Woman Kills Husband with Axe.” It was a city where C.M. Riddell was mayor, but mobsters reigned. Blood flowed like water.

“I don’t know what it was or what was going on, but it was an extraordinarily violent time,” Sullivan said, noting that the police chief even declared the violence had gotten so bad that the department had started staffing patrol cars with four officers each, all with rifles at the ready. “Tacoma had a case of Chicago disease.”

Crime was so rampant that a man lost a race with bullet when a rookie cop mistakenly fired at him. A robbery had just occurred. The cop responded. He saw a man running. He assumed the man was tied to the caper. He yelled. He fired a warning shot. And another and another. The final bullet ricocheted off the rain-slicked street and found its mark. The father of six children died simply because he didn’t want to get robbed, not knowing the gun-toting “robber” was a beat cop out serving and protecting the good citizens of Tacoma.

But it wasn’t just street crime Tacomans had to worry about. Tycoons of finance were just as dangerous, namely the bankers at the Scandinavian American Bank, where one in eight people had their money. The bank’s skyscraper was under construction with great fanfare in the fall of 1920 only to collapse into bankruptcy from the weight of fraud and corruption that strained its ledgers and bled into the pages of newspapers up and down the coast after the New Year, just as Hammett left to rejoin the Pinkertons and later begin his writing career.

Hammett would never return to Tacoma, but the recollections of his time here would provide the threads he needed to weave together his crime tales. The city’s name actually only appears in one Hammett work, however, that of the “Flitcraft Parable,” a short aside in the “Maltese Falcon.” The story has a chap named Flitcraft having a near-death experience only to abandon his life and family in Tacoma. With children to care for, his wife hires a detective to find him. Flitcraft turns up in Spokane. He is living a life strikingly similar to the one he fled in Tacoma, creating a parable about chance and destiny.

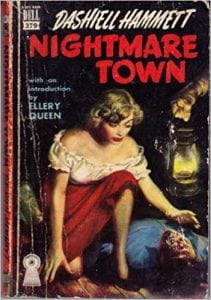

Hammett’s ode to the City of Destiny – albeit not by name – can be found in “Nightmare Town,” a short story filled with backroom deals, cops on the take and buyable politicians who ruled a seamy city of gambling halls, brothels and flop houses.

“Tacomans from that era would have recognized their city in that story,” Sullivan said.

Now sure, there were other hard-boiled writers of the time, with Carroll John Daly also often getting nods as the father of the genre. The paternity suit has defensible evidence from all sides in all ways. But let’s face it, Hammett’s Sam Spade comes to mind more often than any of Daly’s detectives. Hammett also was an Army veteran and former detective before he tapped out his real-life adventures in his detective fiction. Daly could never make such a claim. He also failed to ever visit Tacoma.