Everything seemed simple enough.

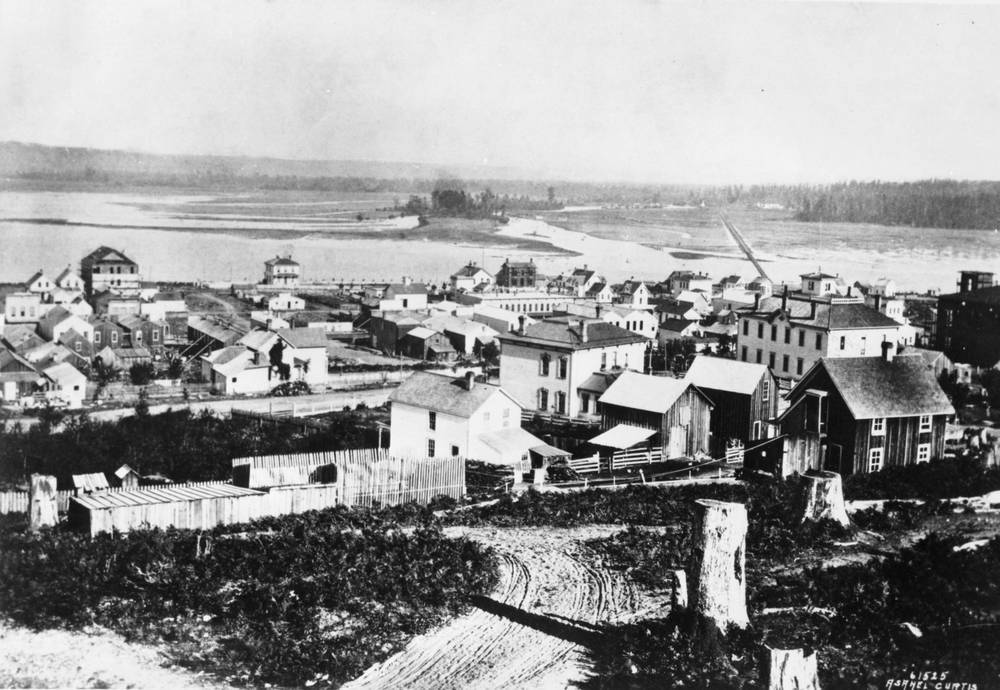

The Northern Pacific Railroad had selected largely virgin forest land along the hillside of Commencement Bay to be the terminus of its transcontinental tracks in 1873. All the tycoons needed then was someone to draw a bunch of property lines on a map so people could buy lots, build homes or businesses, and carve out roads from the wilderness.

But life is never as easy as it first seems. Drafts and designs came and went, until the least inspired grid system won out over a design that could have been model for other cities around the world. The story from grid lines to awe-inspiring vistas and back-to-basic blocks is one of lost opportunities and the need for profit over anything else.

The first person assigned to map out what would become the City of Destiny was James Tilton. He was an obvious choice. He had been surveyor general under Territorial Gov. Isaac Stevens a generation prior and was certainly qualified to draw up where parcel lines and streets would go in a little backwater town on Commencement Bay.

Few records of his original work survive, but the late Murray Morgan wrote about how rudimentary his design of the fair city was in his telling of the whole episode in his book “Puget’s Sound: A Narrative of Early Tacoma and the Southern Sound,” that was recently rereleased with a new forward by Michael Sullivan. “An account in the Weekly Pacific Tribune for October 3, 1873, indicates he made a few modifications to the basic grid plan then in vogue,” Murray wrote. “Three main avenues 100 feet in width paralleled the waterfront. Two others slanted diagonally up the face of the hill, a concession to the difficulties of horse-drawn street-cars, not to mention pedestrians, would encounter on a direct climb. The five avenues were flanked by blocks 120 feet deep which ended in 40-foot-wide streets, too broad to degenerate into alleys but not grand enough to detract from the designated thoroughfares.”

Tilton’s Tacoma was not to be, however.

The railroad was hemorrhaging money and teetering on the verge of bankruptcy. The venture needed cash, and selling land in its planned boom town seemed the fastest way to turn the green of the Evergreens into the green of hard currency. The railroad set up a subsidiary, the Tacoma Land Co., to start selling lots under the management of Charles Wright. Wright was a bold businessman, and Tilton’s plan was plain and safe. Wright then set out to hire the period’s most noted landscape architect, Fredrick Olmsted, who had just designed New York City’s Morningside and Central parks.

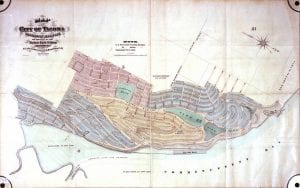

The thought was that Olmsted’s name recognition alone would wow newspapers around the nation and spark a boom for land in a region of the nation that was already being branded as heaven on earth. But the railroad needed a plan. And they needed it fast. Olmsted had just six weeks to submit his plans, a fact that meant he didn’t even have time to visit Tacoma. He mapped out the city from an office in New York by using surveyor reports, drawings and less-than-detailed maps that were drawn by sailors, not land speculators. Olmsted met his deadline and drafted a layout of Tacoma that created city blocks of various sizes and streets that curved and bent rather than darted straight into t-shaped intersections.

It was described as “unlike that of any other city in the world,” in Pacific Tribune, whose publisher Thomas Prosch also wrote that it was “so novel in character that those who have seen it hardly know whether or not to admire it, while they are far from prepared to condemn it.”

Olmsted’s plan had his signature feature, a park that would define the city, much like his Central Park design in the Big Apple.

Land speculators weren’t happy. They wanted a grid system that provided big lots at prime intersections that overlooked the water. Curves didn’t provide corner lots, and Olmsted’s vision was filed with slopes and curves. Some called the plan less of a design for a city and more like a drawing of “a basket of melons, peas and sweet potatoes.”

Since the real estate investors weren’t happy, the railroad executives weren’t happy, so plan had to go. The railroad moneybags needed land speculators to have smiles on their faces as they emptied their wallets to purchase lots in the fledgling timber town. The big wigs at the Northern Pacific sent Olmsted a letter simply and firmly stating that his services were no longer required.

With little time and even less money to commission yet another design of the city, the front office revisited Tilton’s plans. Curves and slopes were out. Grids and lines were in. Square and rectangle lots went up for sale weeks later, just in time to save the railroad from financial ruin. The plan kept some of Olmsted’s features, particularly the grand boulevard of Pacific Avenue as the main roadway for the city, but most of the rest was scrapped.

His vision of a city with curved boulevards and grand parks, was not wasted, however. They just were used in a different city, albeit temporarily. See, Olmsted would design the space for the Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, which included the key landscaping elements he drew out for Tacoma. That world expo would inspire city planners and architects for a generation because it helped redesign the use of public spaces and parks in how cities function and serve their residents. Tacoma could have been that inspiration if only the railroad hadn’t needed quick cash from the sale of square lots on a grid.