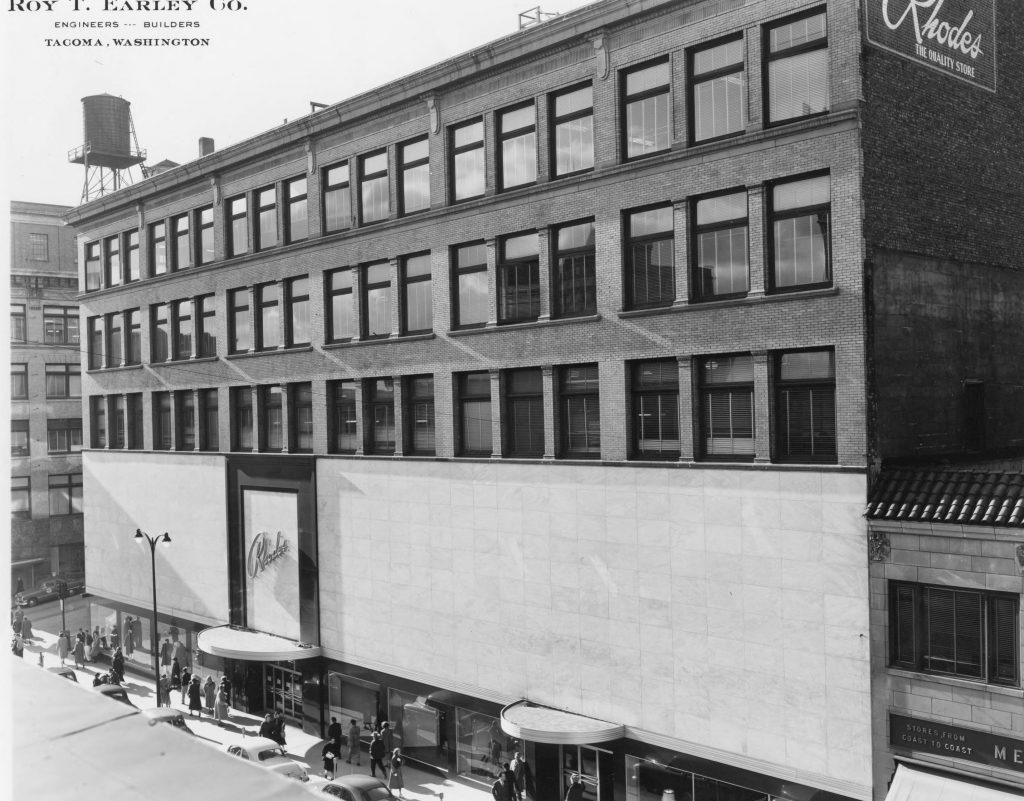

In March 1940, Isabel Franklin, home economist for Tacoma City Light, led a free daily cooking school at Rhodes Brothers Department Store’s fourth-floor model kitchen. Co-sponsored by the store and City Light, the class was entitled “Easter Food and Fancies.” Guests could get recipes for a complete Easter breakfast, as well as Bishop’s bread, pastel-tinted sugar, Easter eggs (just like great-grandma used to make before commercial dyes!) and a fancy dessert shaped like a calla lily. They learned all these recipes simultaneously while finding out about the wonders of cooking with electricity.

Across the country during the first half of the twentieth century, businesses and governments teamed up to promote the latest cooking technology. Tacoma embraced this trend because it promoted the city’s reputation as a modern city (and boosted local business). Stores printed advertisements, published recipes and held demonstrations and classes, sometimes called “cooking schools.”

Before the advent of gas and electricity, stoves were heated with wood and coal, a complicated art because these stoves required a large amount of fuel and lacked precise temperature control. That is why old recipes rarely include baking times and use vague temperature measurements such as a “quick oven” or “slow oven.” Thus, cooking with gas or electricity meant learning new ways to prepare food. Buying new appliances was expensive, and many people saw it as unnecessary. So, businesses’ sales tactics were often aggressive.

Efforts to get Tacomans to change cooking technologies were spearheaded by what is now Tacoma Public Utilities. In 1893 voters approved city plans to buy Tacoma Light and Water Co. (founded in 1884). The company eventually secured a monopoly on supplying electricity to the city. In the early twentieth century, Tacoma was promoting itself as the “Electric City” because of its cheap electric rates and common use of electric appliances, including for cooking.

At first, however, efforts focused on natural gas. The Tacoma Gas Company held regular classes in their showrooms in 1910, three times a week. In May that year, they even offered a contest. People could send in their answers to the question, “Why gas is the best fuel.” The winner received a free gas range (worth $15).

Gradually the focus shifted to electricity, and the city played a more significant role than it had done with gas. In 1911, the city hall opened a counter to sell electric lights and cooking utensils. On June 23, 1913, the Tacoma Times newspaper described a free public display at city hall, inviting residents “to see what the possibilities are in the line of the warm juice [i.e., electricity].”

However, not everyone in the city was enamored by the local government’s foray into business. In 1915, Mayor Angelo Fawcett protested plans to sell electric stoves, saying it would “defraud” the public because only wealthier people could afford them. After all, it had recently cost him eight dollars to run an electric heater in his bedroom two months while he had been sick.

Still, electricity was crackling to the rise. Department stores, the cutting edge of business at the time, were key promotors of electrical appliances. They started early. In 1911, People’s Store ran a daily cooking school. Mrs. N. M. Reddington taught a lunchtime lecture and demonstration in the model kitchen on the third floor on topics such as “How I Make Cake.”

Teachers at cooking schools were usually home economists, college-trained women who worked for companies, department stores or manufacturers. One of these women was Isabel Franklin. Before moving to Tacoma, she became famous under the pen name “Polly Brown,” working as a home-making expert for a Seattle newspaper.

Efforts to push electricity continued over the years. During the 1930s, despite the Great Depression, Tacoma had among the country’s highest residential consumption of electricity. Manufacturers such as General Electric and even the Tacoma Times newspaper sponsored cooking schools. Companies held contests and gave away samples of groceries to draw people to their cooking classes. For example, to interest people in attending a three-day cooking school sponsored by General Electric in 1940, the paper published sample recipes for popcorn, broiled turkey and angel food cake.

Later cooking schools began to adapt to new technology. In April 1940, for example, Fisher’s Department Store sponsored a cooking school on KMO-Penthouse Radio, broadcasting Isabel Franklin’s twice-weekly classes from the store’s seventh-story kitchen. She used a gas range while teaching the “Penthouse Cooking School of the Air.” It featured local products such as Meadowsweet Dairy products, Jordan’s “fresh-as-a-daisy” bread and Fairmont coffee, tea, spices, extracts and canned goods from the Tacoma Grocery company. In-person attendees could sample the finished recipes and receive free samples of groceries.

While cooking schools are no longer as popular as they once were, companies continue to use educational resources to promote their products and services. As technology changes, they have adapted through television and the internet to teach people how to use new cooking gadgets and appliances, from the microwave in the 1970s to the Instant Pot of today. Our cooking, like our culture, continues to change over time.