Puget Sound played a little-known role in a unique time in history when East Coast orphan found their way on trains bound for farm families in the Midwest and West Coast for almost a century.

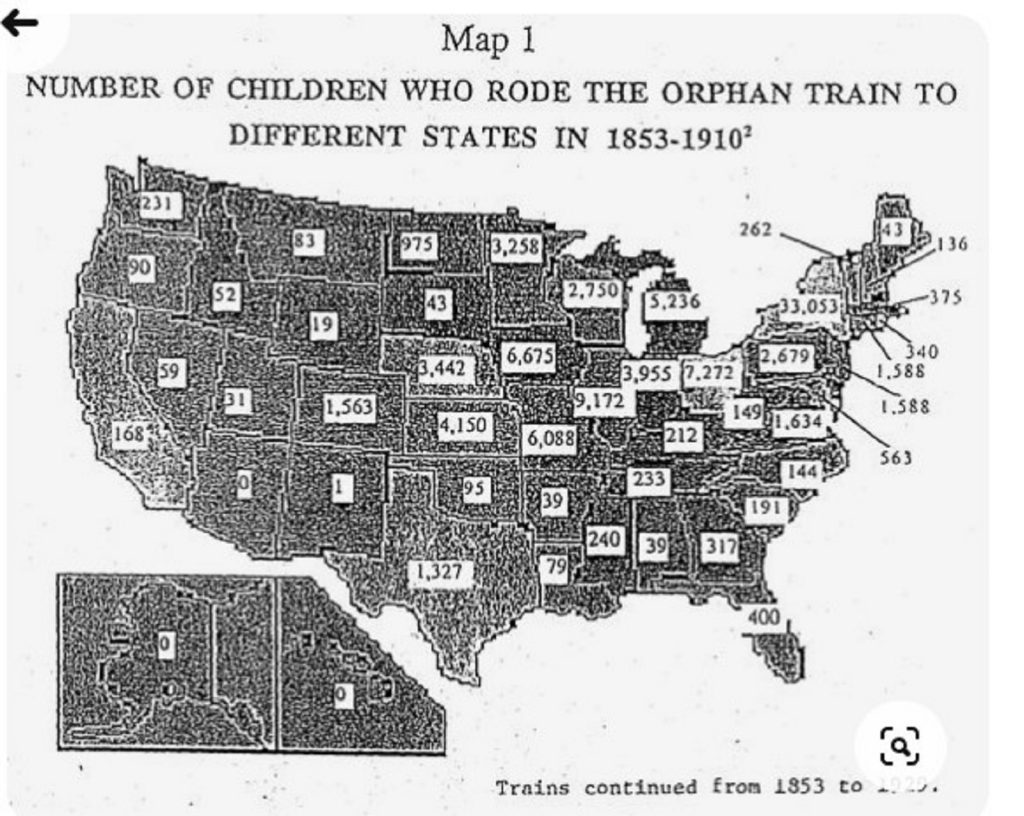

This is the story of America’s “Orphan Trains.” They operated between 1854 and 1929, with about 250,000 children riding the rails to new families around the country. About 231 children ended up in Washington State. Particulars about their stories have been lost to history. Since Tacoma was the terminus for the Northern Pacific Railroad, that made the City of Destiny the proverbial “end of the line” for some of those East Coast orphan train riders.

The Orphan Trains

Flashback to America in the 1850s for a moment. Its large East Coast cities were booming faster than their economies could support, leaving many to live in crowded tenements or without shelter at all. Without the sorts of social services commonly found these days, police arrested children for vagrancy and placed them in adult jails rather than have them rove the streets or be neglected by their parents.

The Children’s Aid Society and the New York Foundling Hospital developed the idea of moving the needy children away from the squalid streets of New York and Boston and into lives in rural areas “out West,” where farms just happen to need hands to plant and pick crops or milk cows. This idea of “placing children out” has gone down in history as the Orphan Train Movement, although about half of the placements involved children who had at least one living parent, and a quarter had both parents, who were deemed incapable of caring for their children.

There were few, if any, formal adoption laws or procedures, during the orphan train era, particularly in the early days, so contracts between the agencies and the placement families fell under “indentured agreements.” Agencies would match East Coast orphans with families after interviews and background checks by charity representatives, as well as character declarations from priests or civic leaders about the host family. At least once a year, periodic visits checked up on the adoptions.

These orphan trains reached every state and even ran to parts of Canada and Mexico. Local newspapers often overplayed the spectacle of the orphan trains coming to town, with descriptions of children being paraded and showcased for prospective families, who then walked away with a child of their choice. While such scenes were documented, they were essentially the exception to the practices of the time.

“You couldn’t just write in and request a kid,” National Orphan Train Complex Curator Kaily Carson said. “It was a little more complicated than that. There were a few more steps.”

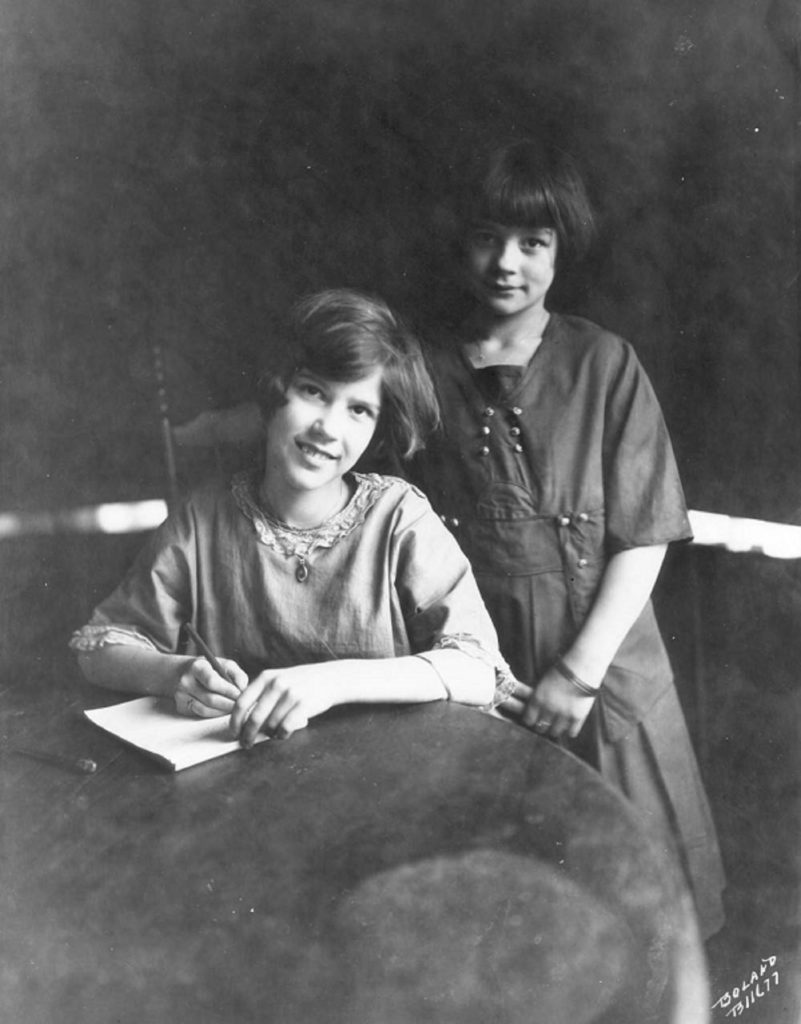

The Children of the Orphan Trains

The collection of orphan train narratives in the NOTC’s records suggests that about 80 percent of the children considered themselves fortunate to have found themselves in new, loving homes. That leaves 20 percent, however, reporting they faced harsh treatment and neglect by their adopted parents, who often considered the children as little more than free labor on their farms. Agents tried to keep siblings together, but prospective parents could choose to take a single child, separating siblings between nearby families.

“All of the kids were facing terrible futures in New York,” Carson said. “A lot of the orphans really did end up in good situations.”

The rise of local, state and federal social programs, stricter rules or outright prohibitions of moving children across state lines for adoptions, coupled with rising criticism about the orphan train system, finally put an end to the controversial practice by 1929.

Of the quarter of a million children relocated during the orphan train era, only a few hundred are living today. Now their offspring and grandchildren are researching their own heritage or gathering details about family stories regarding their ancestors’ childhood.

To that end, the Orphan Train Complex has about 7,500 records, mostly personal accounts. The New York Children’s Aid Society and the New York Foundling Hospital have the largest repository of orphan train documents, and they still operate to this day. They are both understaffed in their archive departments as well as fall under the state’s strict adoption disclosure rules that predominantly release records only to family members.

Tacoma and the Orphan Trains

Tacoma Public Library not only has a collection of fiction and nonfiction books on the orphan trains, but it also retains records from local orphanages and hospitals for unwed mothers that provide further glimpses into this aspect of the local history of orphanages. Among the library’s Northwest Room collections, for example, is “Children’s Industrial Home Records, 1900-1944” which includes its register of children and scrapbooks of its facilities.

In a story that comes full circle with the orphan train era specifically, the library has information about the Whiter Shield Home. It was a hospital for unwed mothers that dates back to 1890. It formed when local doctors Eva St. Clair Osburn and Ella Fifield learned about a young girl in labor on the streets of Tacoma after the hospitals refused to admit her because she had no money to pay for the birth. The woman took her in and birthed her child after finding her at a train station.

In 2019, the White Shield Home, which had long been closed, was listed on the city’s landmarks roster for its historical and architectural significance and ties to the effort of two of the area’s earliest female physicians.