Puget Sound was once the center of commercial fishing in the Pacific Northwest. It ranked alongside timber before the turn of the last century only to then suffer from overfishing and environmental degradation.

Salmon was the staple of the Native American tribes along the Salish Sea for more than 12,000 years. Centuries came and went with tribal bands and villages pulling together to harvest salmon during the annual fish runs—food that would be cleaned, smoked and stored to feed mouths throughout the winter.

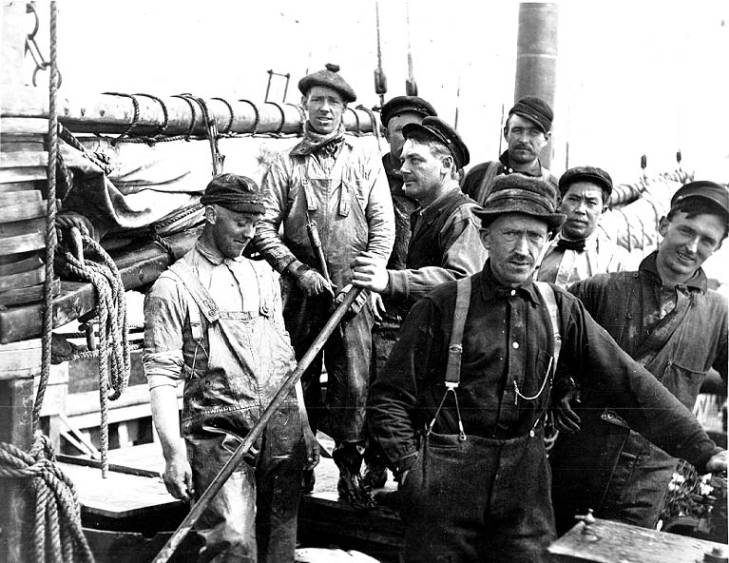

European and American traders and settlers then swarmed into the area in the late 1800s. The influx of white settlers changed everything. Giant wooden ships soon filled their hulls with tons of salmon each season for sale back East and down the coast. Hapgood, Hume and Co. established the first fish cannery in the region in 1866. American fishermen soon commercialized the fish harvesting process, with some 30 fish canneries in the Pacific Northwest by the 1880s. Local salmon found its way around the globe at an unregulated rate that was far from sustainable.

The population boom of the 20th century then cut the salmon runs at the source, with overdevelopment near, and the rechanneling of salmon-baring rivers and streams. Both overfishing and lost habitat bit into the salmon counts from their respective sides of the river-to-ocean-back-to-the- river cycle.

Industrialization of the harvesting process made fishing faster, easier and more profitable. Boats got bigger, so captains could catch and store more fish before heading to their paydays at local canneries in the late 1940s through to the 1970s. Fishing boats, however, also had to travel further and further out to sea, making trips longer and more expensive for potentially smaller hauls. Environmental regulations and fishing restrictions caused many operations to shutter their doors.

The plummeting fish supply and the rising call of Native American tribes for the federal government to uphold its treaty obligations with the sovereign nations regarding their fishing rights brought a host of efforts to bring fishing stocks back from the brink of extinction. Most notable of those efforts came after the landmark U.S. v State of Washington case, better known as the Boldt decision. That 1974 federal decision concluded that the local tribes had claim to 50 percent of the salmon and steelhead harvest and fish management should be jointly coordinated between the tribes and the state under the terms of the treaties signed in the 1850s, namely that “The right of taking fish, at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations, is further secured to said Indians in common with all citizens of the Territory.”

After decades of legal, political and even physical fights over the dwindling fish stocks, Puget Sound tribes created the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission to work alongside state agencies to manage salmon resources and habitats. Despite these efforts, fish populations continue to decline. Salmon in Washington, California, Oregon, and Idaho were already extinct in about half of their historic spawning areas. All but two of the Northwest’s half of a dozen salmon species are federally listed as either “threatened” or “endangered” because of what is referred to as the “Four Hs,” habitat destruction, hydroelectric dam construction, harvesting more than is sustainable and competition between hatchery and wild fish. Many believe the outlook is grim.

“It will never be at the level it was in the past,” Everett Hill said. “We took advantage of the fish for far too long.”

His father, Harper, was a public school teacher and operated a fishing boat during summers and weekends as a side business for decades. Hill worked the lines and traps from an early age.

“It was very hard work, but we loved it,” he said. “The show ‘Deadliest Catch’ isn’t too far off. It was dangerous, but I got to spend time with my dad, and as a kid, I had stories that my friends never had.”

Some family-owned boats remain, but many others are affiliated with larger operations. Various boats run sport fishing tours for anglers in search of landing a prized salmon on their hooks. Until the rivers are restored and pollution abatement efforts take hold, the rise of the fishing industry will remain a question mark in museums like the Harbor History Museum and the Foss Waterway Seaport.

But what is clear is Northwest salmon will be king for a long time to come, in one way or another.