In 1906 a bustling small community of around 50 tar paper-covered buildings sprung up near Sequalitchew Creek in Pierce County. This temporary development housed the families of workers building a new explosives manufacturing plant. From this simple beginning would spring the modern City of DuPont.

The DuPont Company was founded nearly a century earlier in Delaware by a refugee from the French Revolution. The company prospered and had expanded across the country by the turn of the 19th/20th centuries. With its booming construction and industries, the Pacific Northwest seemed the next logical place for business growth.

DuPont Company officials picked the region near Sequalitchew Creek in Pierce County with easy access to Puget Sound and major railroad networks. This area had been home to a Hudson’s Bay Company trading post, Fort Nisqually. After its closure in 1870, the area was farmed by former employee Edward Huggins and others. By 1906, he was getting on in years and ready to retire. He sold his land to the DuPont Company and moved to Tacoma.

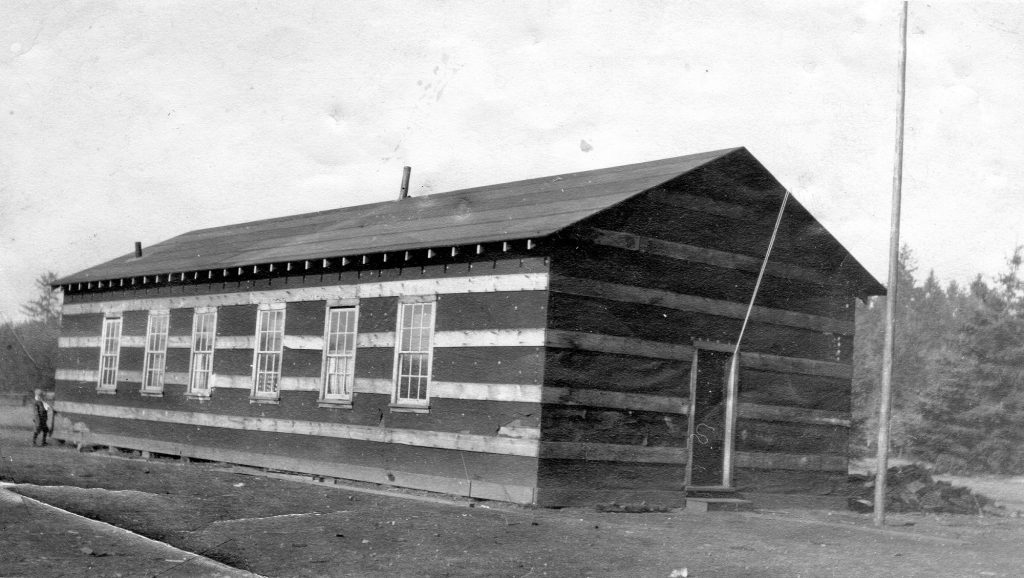

Construction on the explosives plant began in 1906. It took hundreds of workers to construct the factory. Many of the workers were recruited locally and were single. They were housed in a tar-paper boarding house. In 1906, newspapers were full of advertisements for construction laborers for “Huggins Crossing.” By the following year, the community was called DuPont, after the company. It was the only DuPont plant named for the company itself.

Many other workers, however, were skilled laborers transferred from Company plants across the country. The married men soon sent for their families. These families lived in tar-paper-covered houses. The small temporary buildings were cheap to build, though far from comfortable. Newspapers and blankets decorated walls and provided some insulation. The tar paper helped keep out the rain.

The tar paper village, later known as “Old Town,” quickly became an entire community. It was home to a diverse group, with many workers being immigrants from Scandinavia, the United Kingdom, Germany and Italy. The former Huggins home (Fort Nisqually Factor’s House) was turned into a community center. Club meetings, religious services, Sunday schools and events were held there. This included the community’s first wedding between the matron of the boarding house and one of the construction workers.

The Olympia Daily Recorder described an upcoming community Independence Day celebration in DuPont in 1907. Joking that “the day will be as noisy as the purpose of the plant would suggest,” a ballgame, races and a ball were planned.

Many children called “Old Town” their home. School District No. 7 built a thirty by sixty-foot tar paper schoolhouse for them. The building was divided in half by a cretonne curtain. This school would be replaced in 1911 with a simple wooden building at what is now Barksdale Station. A brick Federal Style school would be built next door in 1917. That building remained, with expansions, the DuPont School for decades. It was demolished in 1989.

Work on the plant, however, stalled. A nationwide financial panic halted construction in October 1907, and building could not resume until the next summer. Local newspapers remarked that many families were forced to move out when the work had stopped. DuPont Powder Works finally began production in September 1909.

After starting production, the company began building a new permanent community, a safe mile from the plant’s gates. “The Village” was a planned community and a true company town. The DuPont Company owned the land and buildings, renting them to their occupants. The town’s three businesses, a meat market and two general stores, were independently run (the meat market is now home to the DuPont Historical Museum). The town also had a volunteer fire department, clubhouse and a church (now Community Presbyterian Church of DuPont). Many workers spent their entire careers at the plant and remained after retirement.

Fifty-eight homes were built in 1909/1910, and the village continued to expand throughout the next decade until it included about a hundred houses. In 1917 six houses were even moved from the land condemned to make Camp Lewis (now JBLM). Except for the large homes of the plant superintendent and assistant superintendent, workers’ homes were nearly identical, though varied by the number of rooms. Roads (originally dirt) were named for company plants across the country. For example, Barksdale Avenue, the village’s main street, is named for the Wisconsin plant that many of the original workers came from.

Unmarried workers lived in the forty-one-room Hotel DuPont, located on Barksdale Avenue between Hopewell and Penniman Streets. In the mid-1920s, 125 men boarded at the hotel. It was demolished in 1930.

Even as commuting became more popular, most workers continued to live in DuPont. The community was close-knit, and everyone who lived there was connected to the company. In 1951, the company sold the houses to its occupants and the community incorporated.

More changes would come in 1976 when the company closed the DuPont plant due to market changes. Over its decades of operation, it produced over one billion pounds of explosives. The company land was sold to Weyerhaeuser, who eventually developed Northwest Landing, a commercial and residential development that more than doubled the size of DuPont. The community has come a long way from a collection of simple buildings clustered around the historic 1843 Fort Nisqually site.