No markers sit along Tacoma’s waterfront. No statues honor the victims, and no plaques memorialize their names. But their story is told for all who are willing to hear the whispers of the dead.

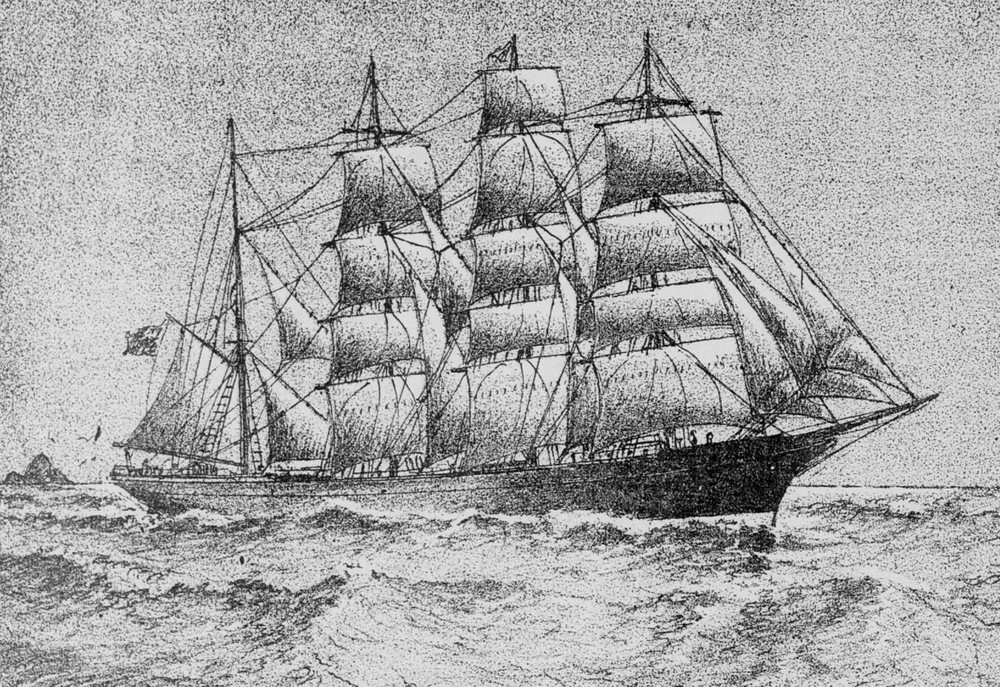

Tacoma’s largest maritime disaster occurred under a cloud of mystery in 1899. The British, four-masted barque was moored in Commencement Bay, about a half mile off the shores of what were the St. Paul and Tacoma lumber docks. The 10-year-old vessel had traveled the globe, from Liverpool to Calcutta to New York and Shanghai. It had raced from Hong Kong to San Francisco in 31 days in 1892 and from New York to Yokohama in 119 days with a cargo of case oil in 1895. The 304-foot vessel shuttled from Shanghai to Port Angeles in just 47 days and then sailed to Tacoma days later. It emptied its load of steel and prepared to fill its hulls again with Queenstown-bound wheat. It would never leave the City of Destiny, creating fodder for ghost stories that remain to this day.

The crew of the Andelana moored the empty-bellied lady to heavy logs and went to bed for the night in the safety of the sheltered, deep-water bay. All was calm for a while. Eventually a storm brewed, however. The ship later began to pitch and sway. The waves amplified the rolls because the hulls were empty, making the ship seem more like a cork floating on rough waters. The ship tugged and strained against the chains that moored it in place. Something had to give. The ship was under the waves by dawn. Its 17-member crew was never seen again. No witnesses saw what happened.

News of the sinking quickly rippled through newsrooms around the world with accounts appearing in newspapers in California and New Zealand.

“There is no doubt that when the terrible gale sprang up last night, she partly turned over. This lifted her starboard ballast log out of the water and the weight caused a defective link to break,” an account in the San Francisco Call recounted the next day. “Thus released from the log, the ship turned suddenly on her beam ends, and in another instant the water was pouring down her hatchways. These were but loosely covered and afforded no protection. With her toppling masts and towering side to give the gale full swing, the Andelana went over as though she were a racing shell. How the seamen struggled to escape can be imagined, but without doubt they had scarcely leaped from their bunks into the inflowing waters before their vessel had struck bottom, twenty-three and a half fathoms below the surface. This is indicated by the fact that the vessel did not drift from her mooring place but sank almost at the spot where she was moored last night. With daylight this morning, the Andelana was missed. Wherein she had been riding, apparently secure, at dusk last night there was but a blank stretch of waters.”

The only evidence a ship ever anchored in place was a swamped lifeboat that was found on shore, a bobbing mooring log with its broken chain still attached and a mattress bearing the Andelana name that was found floating in the water.

Investigations later determined that the ship, which had been made top heavy because of the empty hull, broke from its mooring and capsized in the storm. The entire accident likely took a matter of minutes. Its story remains, however, largely because it marked the largest shipping disaster in Tacoma and the fact that the ship was never raised and salvaged. The ship and the 17-member crew still rest on the floor of Commencement Bay.

“They think it is still under there,” Tacoma Historical Society treasurer and author, Deb Freedman, said. “They think they can still find something.”

Freedman authored a book, Rising up from Tacoma’s Twenty-One Disasters and Defeats in 2015 that lists the Andelana among the roster. Its story is also mentioned in Tacoma’s Haunted History, by Ross Allison and Teresa Nordheim.

Since the ship was empty, any modern salvage operation would only find some rotted wood and rusty iron. The only known relics from the ship are the handful of gavels used by Republican clubs in the region that were reportedly forged from iron rails that divers retrieved in 1954 and a port window in the collection of the Washington State Historical Museum. The Tacoma Historical Society had a relic of sorts on display years ago, however. It was a scale model of the Andelana that a man had carved from a piece of wood salvaged from the streetcar disaster of July 4, 1900 that left 44 people dead. The rather macabre art bound the city’s worst maritime disaster and the nation’s worst streetcar tragedy, which happened just a year later, into one artifact.

“Those two disasters were so close together,” Freedman said. “For a legacy, that is a little unusual.”

Like all disaster stories tales of coincidences and close calls surround the Andelana as well, facts that further feed into the retelling of its story either as history or as a ghost story around campfires. The captain had expected his ship would be towed into the loading berth the following day and was invited to have dinner ashore. He declined the offer, saying his place was aboard the ship. He would drown hours later. A ship’s apprentice went ashore to find a doctor to treat his abscessed tooth. He was there when the ship sank. The ship was lightly crewed since ten of the men had signed on to serve aboard another ship earlier that week. All who remained perished.

One of the eeriest stories about the Andelana is that the dead are photographed in a single image. Maritime photographer, Wilhem Hester, had taken the photo the previous day. They were all dead – including the dog – by the time the photograph was printed. The story goes that Hester was devastated and refused to photograph entire crews through the rest of his career, demanding that at least one member step out of the frame before he snapped his shutter.