Anyone who researches history will know that the past offers more than facts and dates. Cold, hard times and figures can lead to different conclusions, since just straight information can be interpreted many different ways. Absent context, conjecture becomes rumor and then rumors get repeated enough to become theories and then urban legend.

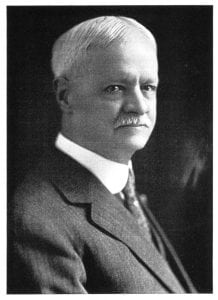

Such is the case with William Ross Rust and the mystery surrounding the death of his son, Howard, and the ramifications it had on the family. Rumors and theories abound. Facts about the Rust family are less abundant.

Such is the case with William Ross Rust and the mystery surrounding the death of his son, Howard, and the ramifications it had on the family. Rumors and theories abound. Facts about the Rust family are less abundant.

“There is surprisingly little about them considering how prominent the family was,” said amateur historian Eric Herbel, who has spent months researching the family. He noted that such an iconic figure of Tacoma’s business circle was decidedly low key when it came to media coverage during a time when any travels or news from any member of the “social class” made the daily newspapers. But with Rust, there are only passing mentions. But those mentions are enough to provide a glimpse into the world of the ultra rich during the turn of the last century—and hint at a cover up of a criminal conspiracy in some circles. “I just don’t have enough evidence to say either way.”

Rust came to Tacoma in 1889 to buy and immediately expand the Tacoma Smelter and Refining Co. He made his fortune smelting copper at what would later become the infamous ASARCO plant along Commencement Bay that caused the lead and arsenic contamination around Puget Sound that will take generations to correct. But little was understood about environmental pollution when Rust owned the plant, and he was considered by most to be a man of vision and a bringer of jobs. The City of Ruston is named after him, after all. The rising demand for copper in the region made Rust a wealthy man, particularly when he sold the plant in 1905 for $5.5 million.

He leveraged that wealth to build Tacoma’s grandest home. Called Tacoma’s White House, Rust’s lavish mansion at 1001 N. I Street was designed by noted architect Ambrose Russell and offered neoclassical style that spared no expense – marble fireplaces, mahogany staircases, ballroom floors and brass fixtures. The mansion spanned 11,000 square feet at a cost of $122,000, or 200 times the average home cost in the City of Destiny in 1905. The home had the makings of a fairy tale, but soon became the site of heartache and a persistent rumor.

Rust’s son Howard died in 1911. He was a few days shy of his 25th birthday. Some accounts said he died of a heart attack at a ranch in Eastern Washington. Other accounts said he collapsed on the porch of the house. Newspapers of the time were surprisingly silent on the matter considering the heir of Tacoma’s top industrialist died suddenly.

The Tacoma Times, for example, contained only a passing notation:

“Howard L. Rust, son of W. R. Rust of this city ruptured an artery in the heart while conversing with friends Saturday evening at Ranford, Wash., and died almost instantly. He would have been 25 years old yesterday. His parents are on a return voyage from Europe now. Young Rust went to Hanford on a ranch to build up his shattered health. He seemed to be gaining until the collapse came Saturday night. He came to Tacoma with his father when four years of age.”

The prevailing story has it that Rust and his wife Helen were so distraught about his death that they could no longer live among the memories of their dead son and set out to build a second mansion to have a new start. What is known is that they sold their I Street house for less than half of they spent on it six years earlier and set out on the construction of a second mansion a few blocks away. The second Rust mansion, at 521 N. Yakima Avenue, was no less lavish and spanned 9,000 square feet.

But some people don’t accept the prevailing storyline. Rumors that Howard didn’t die of a heart attack but actually committed suicide – or worse – have been floated and whispered for more than a century now.

Seattle author and freelance writer Tami Jackson researched the rumors a few years ago and believes there just might be enough to the story to make a case that Howard was murdered – or at least didn’t die from a heart condition. Her narrative about her 2011 research makes for some fascinating reading and adds some speculative flesh to the bones of the few scraps researchers have been able to piece together.

She points out, for example, that it seems odd Howard’s death was not more widely covered with media accounts and that Rust never made a statement or endowment to preserve his eldest son’s legacy. Howard simply disappears from history, unlike Charles Barstow Wright’s tribute to his daughter Annie with an endowment toward a private school that bears her name to this day or Hugh C. Wallace’s 1905 gift of a clock in what is now Old City Hall in memory of his daughter.

“My question to you, dear reader, is if Howard’s death was truly due to a heart problem, as listed, then why did his father omit his name from all future public records?” Jackson wrote. “Would a loving father not want to keep his son’s memory alive – forever?”

But there is nothing of the sort.

The Rust mansions remain private residences, although the second Rust mansion is currently up for sale. Owned by the Williams family since the 1960s, this piece of Tacoma’s history is available on the market for $1.7 million.

Dax Williams grew up in the house and still uses it as a local office of the family’s Williams Properties apartment rental business. He really didn’t have any childhood stories about growing up in a historic home so steeped in Tacoma history. To him, it was just a house.

“When you grow up in the environment, it all just felt like a normal childhood home,” he said.