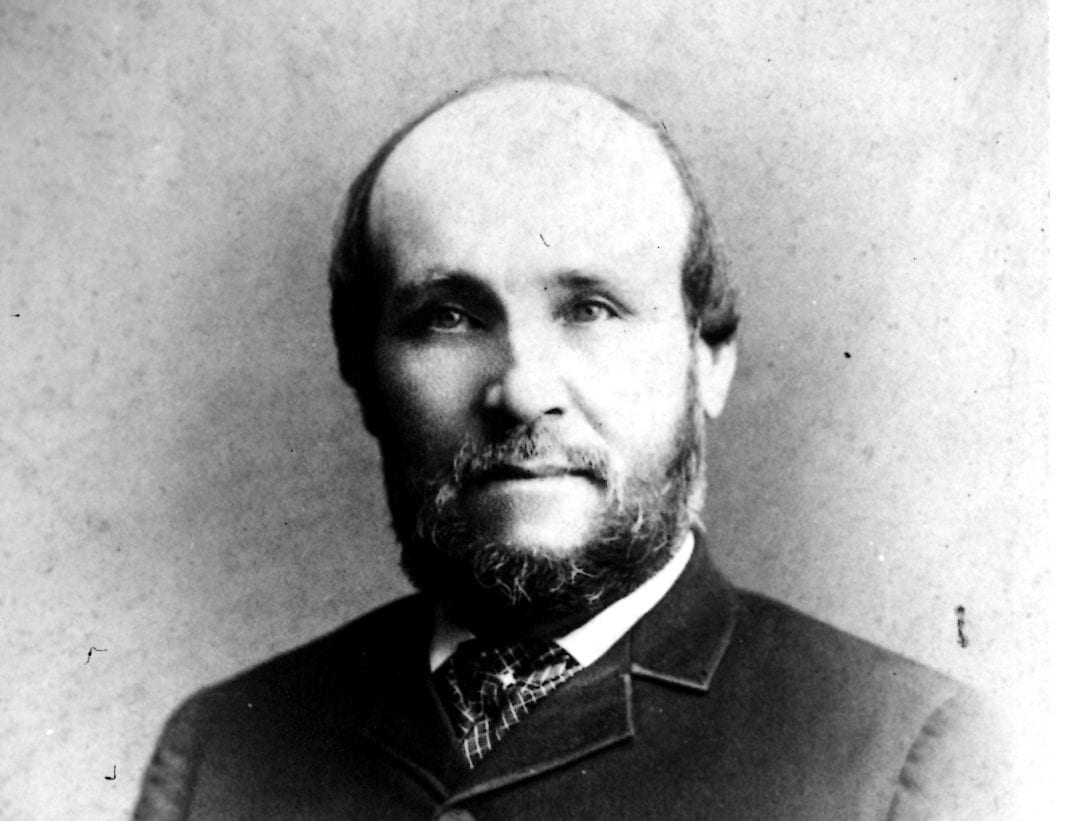

Without the writings of Edward Huggins, we would know much less about life at Fort Nisqually, a Hudson’s Bay post in Pierce County in the mid-19th century. He knew this history because he had lived it.

Huggins was born to Edward and Ellen Chipp Huggins on June 10, 1832, in London’s Southwark borough. He grew up in poverty, attending the Queen Elizabeth Grammar School in London. While still a young teen, Huggins took a job at a ship broker’s office. With few prospects, he signed up with the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), a British fur-trading company that operated in North America. He sailed from Britain in 1849, at the age of 17, never to return home.

The young Englishman arrived at Fort Victoria, an HBC post on Vancouver Island. Shortly thereafter, he was transferred to Fort Nisqually on the Puget Sound, a trading post located at what is now DuPont. Huggins worked as a clerk and bookkeeper at the Fort and also managed the trade shop. Eventually he became regarded as post commander Dr. William F. Tolmie’s righthand man.

Huggins worked at Fort Nisqually during a time of great change. According to the Treaty of Oregon in 1846, the Pacific Northwest became part of the United States. As part of the settlement, the HBC agreed to sell its property and claims below the Canadian border to the federal government. These negotiations took many years.

While the HBC reflected the racism of its time, they were not interested in settling the land, but worked as partners with Native Americans, needing them as laborers and to collects furs. Many HBC workers married Native Americans.

American settlers, seeking land, usually saw things differently. Washington Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens negotiated a series of treaties with Native Americans for the possession of the land. Dissatisfaction with these agreements led to the Treaty Wars from 1855 to 1856. The HBC tried to stay out of the conflict.

The war brought opportunity for Huggins to show his leadership skills. The head of Muck Station fled his post and Huggins volunteered to replace him. Muck Station was part of a series of farming outstations operated by the Puget Sound Agricultural Company, a HBC subsidiary. At Muck, Huggins oversaw other outstations between the Puyallup and Nisqually Rivers, a task that required him to ride between the stations each week alone, which he did faithfully without incident.

After the war, Huggins returned to Fort Nisqually. On October 21, 1857, he married Letitia Work, the daughter of a leading HBC official. She had been a frequent visitor to the Fort to see her sister Jane, the wife of Dr. Tolmie. The Hugginses had a happy marriage and had many children: William, Thomas, Edward, John, Helen, David, Henry and Joseph. After a friend died, they adopted Letitia Williamson.

In 1859, Tolmie was transferred to Fort Victoria and Huggins became the commander of Fort Nisqually. As leader of the post, he faced the difficult task of dealing with increasing American pressure as settlers squatted on company land and stole livestock. In 1869, the HBC finally sold their rights south of the Canadian border. Fort Nisqually closed in 1870.

Because of his long service, the HBC offered Huggins a post at Fort Kamloops in the rugged interior of British Columbia. Huggins preferred to stay, retiring after 20 years of service with the Company and becoming an American citizen. He filed a claim for the Fort Nisqually site. Keeping his home in the “factor’s house,” the Huggins’ farm eventually grew to 1,000 acres.

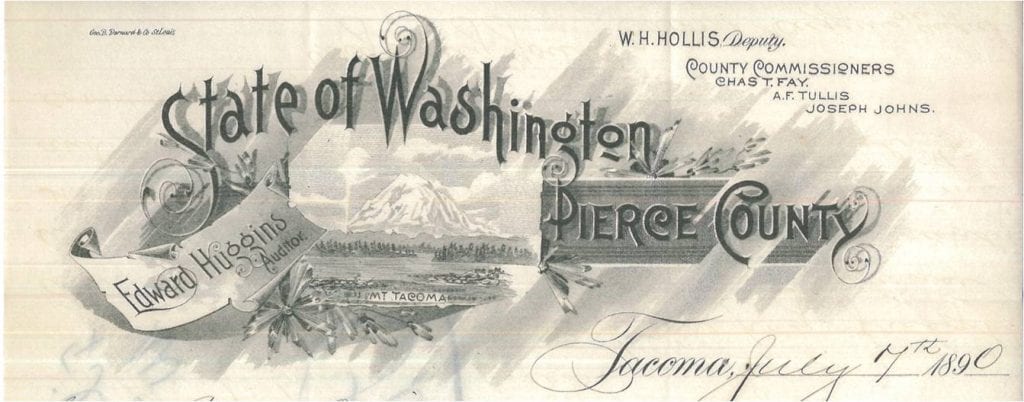

Huggins and his family did not live in isolation. He became active in local politics and was on the local school board. In the 1870s and 1880s, he served three terms on the Pierce County Board of Commissioners. From 1886 to 1890, he was Pierce County Auditor. During this time, he lived in Tacoma while his sons operated their farm.

In 1897, Edward and Letitia retired back to “the ranch.” However, keeping up the farm proved to be too much in their declining health and they reluctantly decided to sell the land to the DuPont Company to build an explosives factory (the origins of today’s city of DuPont) and move back to Tacoma. Edward died January 24, 1907, before their new house had been completed. Letitia passed away on September 12, 1910.

Edward Huggins lived an interesting life and left an inestimable legacy as a historian. He composed essays about Fort Nisqually life for newspapers and wrote many letters. In these writings he tells more of daily life than what appears in official Company records, including that workers at the Fort liked to gather to watch the sunset.

Huggins also preserved the factor’s house and granary from the Fort. These buildings were moved to Tacoma in the 1930s to form (along with reconstructed structures) the Fort Nisqually Living History Museum. This Museum features living history interpretation of the HBC era. The original 1843 Fort Nisqually site, owned by the Archeological Conservancy, is located in DuPont and is sometimes open for tours. The DuPont Historical Museum organizes these tours and also has displays on Fort Nisqually and other DuPont history.