Residents of Pierce County know well the key role the Army and Air Force have played in the area’s history. But there was that one time that the U.S. Navy came to Tacoma’s rescue, when it faced a power shortage that not only threatened the local economy, but put thousands of lives at risk of weathering a cold winter without electricity.

The story took place 90 years ago and changed how electricity keeps your lights on to this day. Back in those days, Tacoma generated most of its electricity from hydroelectric dams on nearby rivers, namely the Green, Nisqually and Skokomish. A small steam plant along the Foss Waterway, when it was called the City Waterway since the Foss name didn’t come about until 1990, added to the water-powered facilities.

All was fine, relatively, for a while. But the area had outgrown the system’s capacity, particularly since it depended heavily on just enough rain and just enough snowpack to keep the turbines spinning. The summer of 1929 was a dry one, however. The fall didn’t prove much better. Water levels were low as the weather began to turn colder. Conservation efforts got stricter. Cascade Paper Co. all but halted lumber production. It laid off the bulk of its workers since it couldn’t reliably power the mill. Camp Lewis even went so far as to command that barracks go “lights out” at 4:00 p.m. to allow area residents to use the power to heat their homes.

Tacoma officials sought solutions to their power crisis wherever they could. They even pled to President Herbert Hoover to come to their aid. Out of that plea came a plan of sending the Navy to the rescue in the form of an aircraft carrier to serve as an impromptu power plant. The Navy didn’t want anything to do with the idea at first. The top brass was won over as negotiations got flowery and conditions got direr, despite protests by Puget Sound Power & Light and also Seattle City Light, saying that there was no power crisis and all was well in hand.

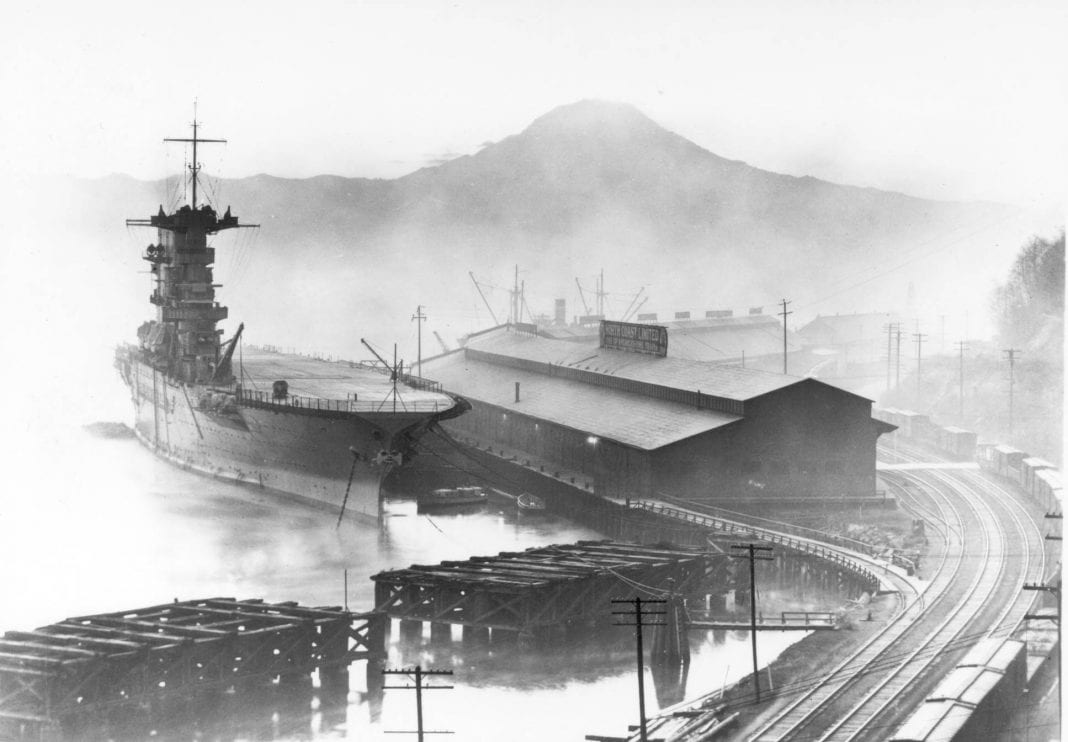

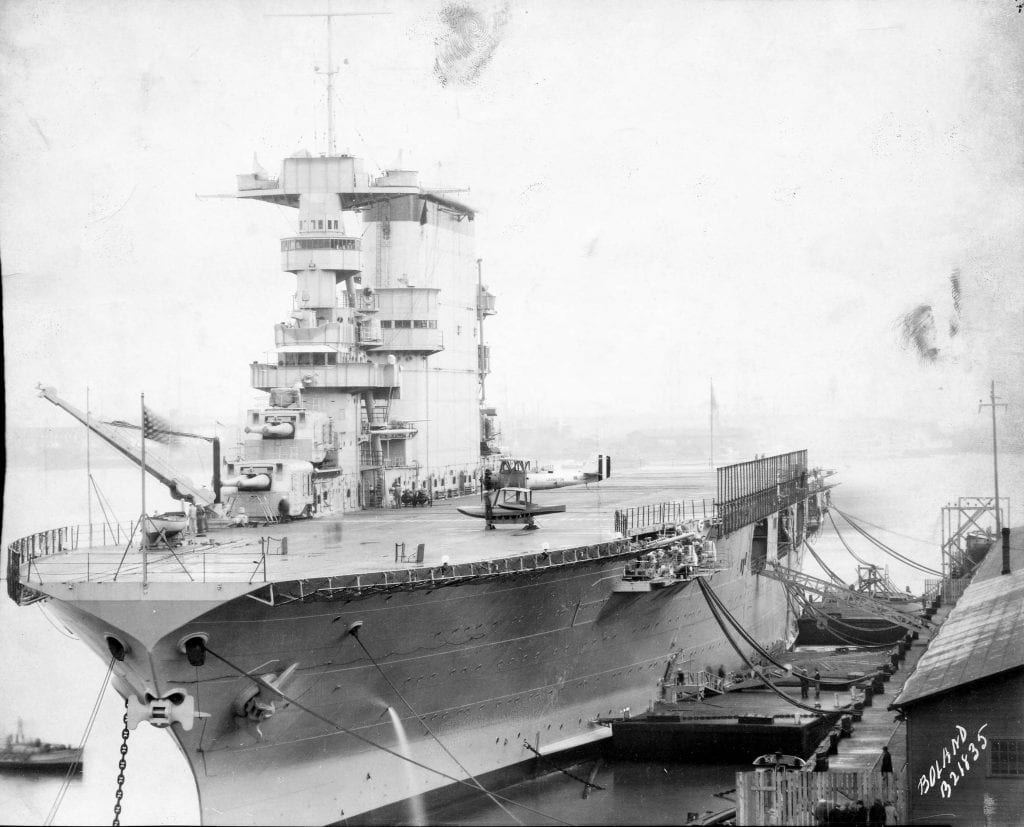

In the face of fact that proved to the contrary, the U.S.S. Lexington steamed from its berth in Bremerton and pulled into Tacoma on December 17, 1929. It was, ironically, raining when the carrier arrived. The wet and cold didn’t stop the band from playing and the crowds from cheering as it docked at the Baker Dock. Onshore transformers connected to the ship’s massive power plant then strung a dozen cables to the city’s existing power grid.

The Lexington’s massive engines would ultimately supply about a quarter of Tacoma’s power for the next month. The carrier’s four steam turbine, propulsion generators created 35,200 kilowatts each, after all. Rather than being an unseen player in local politics and power production, the Lexington became a tourist attraction, with a constant flow of residents getting in-depth tours of the pride of the U.S. Navy. It was just four-years-old and was a ship that gave rise to its own class of warships because of its size and power. The “Lady Lex” was originally designed as a battlecruiser, but was converted to be one of the Navy’s first aircraft carriers as aviation proved to be a rising player in warfare.

Its 1,400 sailors were heroes and treated like visiting royalty during their stay in Tacoma. Dances, dinners and socials around town kept them well fed and well entertained during their stay in the City of Destiny. Freda Gardener of the Tacoma Chamber of Commerce, Ethel Haasarud, a RKO cashier and Naomi Dykeman, the head usher at the Fox Rialto, served as judges for a dance for the Lexington’s enlisted men on the day after Christmas. They gave prizes for the most handsome, most happy and best dancer. The seamen who attended the festivities apparently never even got the chance to sit down because their dance cards were full with the names of single local women by the time they entered the doors.

“This is the first time, in any port, that the men behaved themselves,” a Naval officer quipped in the Tacoma Daily Ledger.

The Lexington would leave a month later after providing 4.5 million kilowatt hours of power from one main propulsion generator, at an average rating of 13,000 kilowatt hours until melting snow and rain brought enough water to the rivers and lakes in the reservoir system to ensure the power crisis was over. See, the new Lexington-class carriers were among the first to have electric-drive motors that allowed their power plants to generate electricity that would then drive powerful electric motors. That fact made it almost perfect for use as temporary power plants wherever electricity was in short supply. It was the first time in history that a ship would provide power for a city, proving the concept along the way. Diving down the internet rabbit hole of the technical side of how it all went down and how it was so rarely repeated can be found at “Going Ashore: Naval Ship to Shore Power for Humanitarian Services, with more detailed play-by-play of the issue available in Naval Records.

The carrier left for San Francisco on January 17. Not wanting to miss out on a good thing, Seattle then asked for the ship to help out the Emerald City with its power issues. The Navy said no.

The “Lady Lex” had a special place in the hearts of Tacomans for a generation, with cards, letters and gifts flowing from the area to sailors on the ship, particularly during the early days of World War II. The carrier would sink during the Battle of the Coral Sea on May 8, 1942. The Lexington was lost to the sea until it was found in 2018 during an expedition that was funded by Microsoft billionaire Paul G. Allen. It sits about 3,000 meters below the surface of the ocean waves that claimed it 500 miles east of Australia.

The most notable other time the Navy came to the rescue of an American city came in 1947, when the USS Foss provided power to Portland, Maine, during a severe drought and a number of forest fires on the East Coast.

To avoid confusion, there were two USS Lexingtons in World War II. The “second Lexington” was another carrier that was commissioned in 1943 in honor of the original “Lady Lex.” It has its own honorable history and museum in Corpus Christi, Texas.