From the very first coughs to headlines finally proclaiming an end to killer flu cases, the medical drama of 1918-1919 involves warnings about the perils of global travel and the limitations of public health. What started out as a group of soldiers listed on sick call at a Midwest training base would lead to a pandemic that would kill more people than the Great War it helped end. This flu pandemic would then disappear and leave a wake of changes in the cities and towns it affected. Tacoma would not be spared.

This is the story of the “Spanish Flu” that would claim roughly five percent of the world’s population and infect one of every three people on the planet a century ago.

Flashback to the waning days of World War I for a moment. Camp Lewis was just a year old and was busy minting soldiers for battle in the trenches “over there.”

Although the origins of what became known as the Spanish Flu aren’t fully known, what is clear is that it wasn’t in Spain. Its “Spanish” moniker only came because Spain was the first major country to report its cases. America, Britain, Germany and France censored war-time reporting of the illness marching through their ranks under the idea that such news would hurt morale and give aid to the enemy.

One prevailing theory of the flu’s origin is that the particularly dangerous and contagious strain of influenza had originated in Kansas in February 1918 after it had mutated and jumped from pigs to humans. During an outbreak there, a soldier went on leave in Kansas’ Haskell County and returned to duty to Camp Funston. Within the month of his return, more than 1,000 soldiers there came down with the flu. Some of the soldiers, unfortunately, had already shipped out to other military installations before they felt too sick to train, bringing the ailment with them. Hundreds of soldiers and military workers then fell ill around the world.

Those vast numbers then brought the contagious disease to the civilian population.

The annual flu season came to Camp Lewis in March 1918, but those cases were largely unremarkable with the soldiers recovering quickly before returning to their training. That luck was not to hold out. News of a devastating flu season was just reaching newspapers. Then the 91st Division left the training fields of Camp Lewis for combat in France in the early summer. Those soldiers were quickly replaced with the newly formed 13th Division. That division drew its members from around the nation, particularly from Eastern and Southern states that had been experiencing flu outbreaks. Those soldiers brought the flu with them.

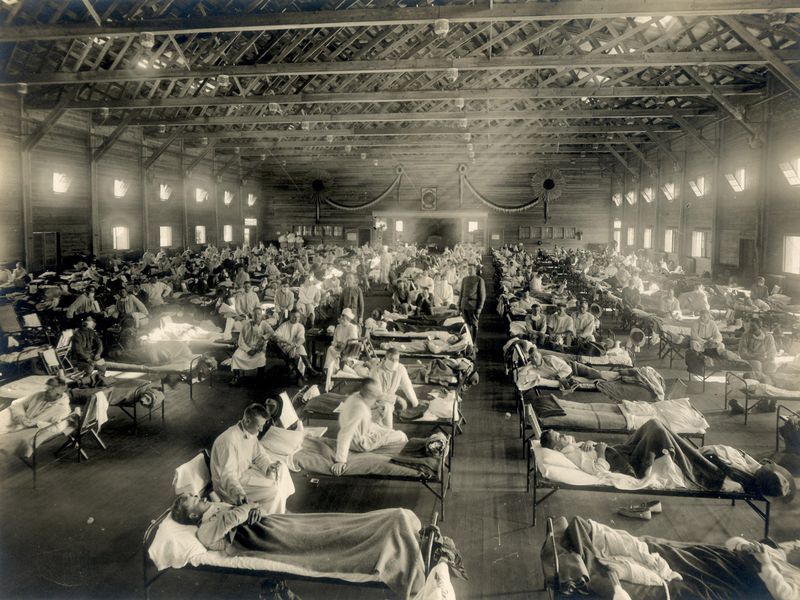

A trainload of sailors from Philadelphia came to Bremerton’s Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, for example, and immediately overwhelmed the military hospitals there. Then Camp Lewis’ hospital beds filled up following the first 11 influenza cases appearing in local hospital records on September 21, 1918. Flu infections then jumped to 1,450 and then 3,024 in a matter of weeks.

Alarm bells rattled at military bases around the nation. All suffered from the strains of sick and dying soldiers. Camp Lewis would close to civilians for an entire month, in the hopes that limiting access would stop the flu from spreading. Tacoma, likewise, would ban public gatherings, public school classes, public funerals and concerts. Other cities around the state did likewise.

“The character of this disease is such that we are in the dark, to a large extent, as to a means to prevent its spread…” the Washington State Board of Health to the governor in its annual report, which was several months late since the board wanted to draft plans to handle the latest news of the emerging crisis. “We know of no way at present whereby we can detect a ‘carrier’ of influenza germs. In fact, we are in extreme doubt as to what germ is responsible for this disease.”

By the time the report was written, the flu had claimed 4,879 lives in just the last three months of 1918. The flu would claim more before it was over. Keep in mind that the prevailing medical opinion of the day was that the flu was caused by a bacteria that could be filtered from being inhaled through the use of cotton masks. These gauge masks actually did little to control the contagious nature of the flu, which is actually a virus that can easily pass through such protection.

The quick action of government officials at least did something since Washington ranked at the bottom of the list of 30 states that reported massive flu outbreaks. Tacoma, for example, periodically closed all theaters, dance halls and banned public meetings in October and November. Only Oregon reported a lower mortality rate from the ailment, most likely because it had much fewer soldiers and sailors flowing into its borders during the peak of the pandemic as America fought a two-front war. One war was in the trenches of Europe. The other one hid behind every sneeze and every cough, often killing within hours.

Camp Lewis and Tacoma were actually under a ban of public gatherings when news of the armistice sparked celebrations in the streets around the world. Some defied the order and attended last-minute parties, but many just stayed home in hopes they could avoid getting the flu from the revelers.

Flu cases would trickle in ones and twos for another a year and a half until the pandemic was officially declared over. It would claim several notable local martyrs. A singer by the name of Linnie Love was among them. The nationally known soprano was booked to perform a spat of shows at Camp Lewis with her costar Lorna Lea right as the flu pandemic filled local hospital beds. They were offered the chance to cancel the shows because of the quarantine, but held to the performer’s credo that the “show must go on.” That loyalty to their craft would lead to Love’s death, however. The duet would perform for the bedridden soldiers only to both fall ill from influenza. Lea would recover. Love would not. She died on November 12, the day after the war ended. She is one of the last of the 164 flu deaths tied to Camp Lewis’ flu outbreak.

One of Tacoma’s first resident priests would also fall victim to the flu because of his devotion to his flock. Father Peter Francis Hylebos, who came to the city in 1880 to serve as the first pastor to Saint Leo’s Parish, was one of the most prominent local victims. He passed away of flu-induced pneumonia on November 28, 1918, the day he was scheduled to deliver a Thanksgiving service at the Rialto Theater. About 500 Tacomans would die of the flu, although the exact number will never be known since reporting standards were not universally followed and varied between hospitals. Most of those deaths occurred in the fall of 1918, but some would trickle in well into the following spring, long after the pandemic was largely deemed to have passed. That fact further clouds the effort to determine a definitive body count. But keep in mind that more American soldiers died of influenza than in combat; 57,000 to 53,000, respectively.

The great Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 provided the world’s first response to a global health crisis and boosted the funding for public health departments around the nation. Preventing flu outbreaks is a mission the Tacoma-Pierce County Health Department continues to this day, with educational and medical programs to vaccinate against the most common strains of influenza.