The Washington State Fairgrounds in Puyallup have a long history of entertainment, education and downright fun. But the fairgrounds are also marked with some of the darkest stains of our nation’s past.

![]() Flash back to the spring of 1942. The United States was at war after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor the previous winter. Americans were enlisting by the thousands, while ships, planes and trucks were beginning to stream off assembly lines. Paranoia and war fever mixed with racism to give rise to Executive Order 9066, which forced more than 100,000 people of Japanese ancestry – whether they were citizens or not – away from their homes and businesses around the West Coast and into “relocation centers” for the duration of the war. Anyone with 1/16th or more Japanese blood was listed as suspect.

Flash back to the spring of 1942. The United States was at war after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor the previous winter. Americans were enlisting by the thousands, while ships, planes and trucks were beginning to stream off assembly lines. Paranoia and war fever mixed with racism to give rise to Executive Order 9066, which forced more than 100,000 people of Japanese ancestry – whether they were citizens or not – away from their homes and businesses around the West Coast and into “relocation centers” for the duration of the war. Anyone with 1/16th or more Japanese blood was listed as suspect.

Tacoma’s bustling Japantown and family farms around the Puyallup Valley, for example, virtually disappeared after their residents were ordered to leave with only whatever personal belongings they could carry. About 1,000 residents left over a single weekend, May 17 and May 18. For others, their first stop into captivity were makeshift shelters at the Puyallup fairgrounds, which the federal government had seized and renamed the Puyallup Assembly Center. It would go down in history by the name “Camp Harmony,” a euphemism given by reporters at the time to give the prison camp an air of happiness during its four months as a transit center for Japanese-Americans from around the state to await their final relocation to internment camps farther inland, namely at Minidoka, Idaho, Tule Lake, California, and Heart Mountain, Wyoming.

Camp Harmony operated from April to October of 1942, and 7,390 Japanese Americans lived in crowded shacks and converted horse stables within its bounds. The camp offered few pieces of furniture and a scarce number of beds, which forced many families to sleep on the wooden floors that were lined with mattress covers stuffed with straw.

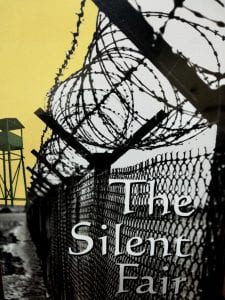

The Puyallup Valley Chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League recently filmed a documentary about the history of Camp Harmony called “The Silent Fair” that tells the story of nine people who were interned there. The group screens the movie to school groups and service clubs around Pierce County. It also offers the film for purchase through its website as a way for current and future generations to learn the lessons from the experiences of their grandparents and great-grandparents.

“You can say ‘never again’ and ‘never forget,’ but it is hard to forget if you never knew,” Chapter President Eileen Yamada Lamphere said. “Our goal is to tell as many people about what happened.”

Her parents met at the internment camp at Minidoka, but grew up in Puget Sound, a fact that she didn’t know much about until she was an adult.

“I didn’t even know I was supposed to ask them question about that time,” she said. “They just didn’t talk about it.”

Her father would go from being classified by the federal government as “4F – unsuitable for service because of race or ancestry,” to an interpreter for the Military Intelligence Service, a wartime predecessor of what is now the Central Intelligence Agency. So, he went from being imprisoned as a suspected spy because he was a Japanese-American and then turned into a spy by the same government by the end of the war.

The last internment camps would close in 1946, but life would never return to normal. The fair would reopen that year, but Tacoma’s Japantown would not. It would never return to the heart of the city’s downtown. Fife’s Japanese community, would likewise, largely resettle in other areas. The effects of those years in captivity would also change family life for generations, Lamphere said.

One change, for example, was the loss of family mealtimes. People in relocation camps would routinely eat by age group in mess halls rather than around family tables. Children who grew up in the camps for the three years of their incarceration then didn’t see the value of family meal time – a practice that they didn’t instill in their children.

“That part of their tradition just doesn’t exist,” she said, a fact she brings up during presentations about Camp Harmony. “It’s just those little things that you don’t learn about in text books.”

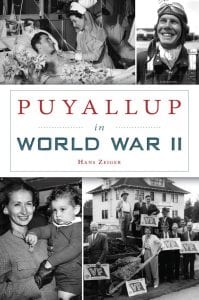

People interested in learning more about the Puyallup Valley during the war years can do so with the Arcadia book “Puyallup in World War II,” by 25th District Sen. Hans Zeiger. The book is flush with wartime photographs of the area and profiles the factory workers, farmhands, soldiers and volunteers who pulled together in the war effort and the Japanese Americans who were caught up in the fervor of the time.