For many, Thanksgiving is a special celebration full of traditions and happy memories. During World War II, Thanksgiving became seen as symbolic of everything America was fighting for, including here in Tacoma.

Long celebrated in New England, Thanksgiving became a national holiday in 1863. In 1939, President Franklin Roosevelt moved Thanksgiving from the last Thursday to the fourth Thursday in November to lengthen the holiday shopping season in hopes of boosting the country’s still struggling economy. People grumbled, but the new date has stuck.

On the Eve of War in Tacoma

In Tacoma, times were hard in the years before the war. The Tacoma Rescue Mission served a full Thanksgiving dinner to 300 homeless men in 1940 at their 1512 Pacific Avenue place. Other groups held informal and cheap parties and dances, like the Poggie Club, which hosted a dance at the Evergreen Ballroom south of Tacoma on the Olympia-Tacoma Highway in 1939. Jimmie Hendrick’s orchestra provided the music.

Hotels and restaurants also offered inexpensive Thanksgiving dinners. Rau’s Chicken Dinner Inn, famous for their butter-fried chicken and located eight miles from Pacific Avenue, was even remodeled just in time for Thanksgiving 1940. The rustic hotel, with the slogan “We feed you, we don’t fool you,” served a whole turkey for every party of ten or more, offering $1.00 a plate for “plate style” and $1.25 per plate for “family style.”

War Comes

Everything changed when the war came. While incomes were up, costs were up, too, and there were shortages of many basic goods. “We don’t have much coffee or tea or cocoa for this year’s Thanksgiving dinner,” reflected the Tacoma News Tribune in 1942, “Many meats are rationed. Assuming that our tires are still useable, there isn’t any gasoline for a very long trip back to the old hometown, and the railroads can’t carry us all.”

Besides that, there were empty chairs at the table as sons and fathers were away at war, even killed. But they had inherited a bountiful nation worth fighting and sacrificing for. “We should find it easy,” the columnist concluded, “even in such a year as this, to be genuinely thankful that we have inherited blessings of democracy that are worth preserving at a far greater price than any that we may have to pay in this war.”

Preparing Thanksgiving Dinner in Tacoma

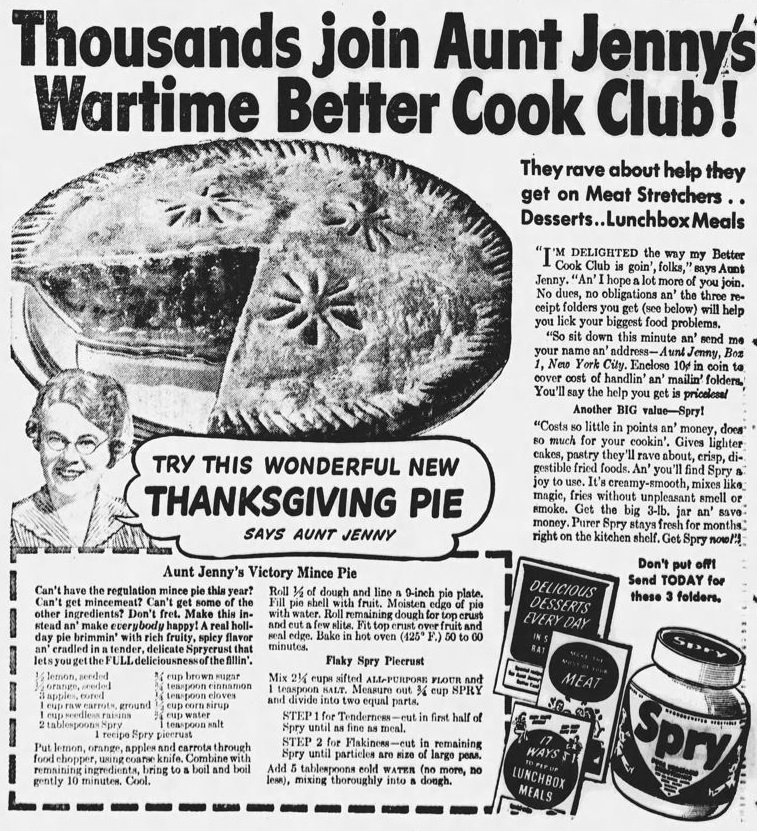

It was impossible not to notice shortages and high prices when making Thanksgiving dinner. In 1942, the Washington Cooperative Egg and Poultry Association, which distributed 75 percent of Tacoma’s Thanksgiving turkeys to stores, had very few small turkeys, but ones over twenty pounds were readily available — for a high cost. People saved up ration points for the holiday and used non-rationed alternatives. Cranberry recipes published in the Tacoma News Tribune in 1942, for example, included cranberry turkey mold, cranberry shortcake, winter fruit tarts and cranberry fruit salad using sweeteners like maple sugar, honey, corn syrup and maple syrup rather than rationed granulated cane sugar. Winter fruit tarts included apple, pineapple, and dried figs.

People were also encouraged to be mindful of how they shopped, not just what they bought. “It’s patriotic to shop early,” urged the local market columnist “Through the Shop with Sue” in 1942. That same year, Sanitary Public Market, 1108-12 Market Street, encouraged women to create “Share Your Car Shopping Clubs” to save on rationed gas and tires. “Let’s help cooperate for victory,” a holiday ad declared.

Hotels and restaurants continued to serve Thanksgiving dinner, but prices went up. The Indian Inn on Pacific Avenue at Brookdale charged $2.00, up from the typical $1.00 to $1.50 of the pre-war years. The last thing anyone wanted to be reminded of in a celebration of American plenty was rationing, and restaurant ads did not mention it. A 1944 ad for Busch’s Triple XXX, 4505 South Tacoma Highway, showed no signs of rationing, offering roasted turkey and sirloin steak alongside holiday staples like homemade cranberry sauce, whipped potatoes and pumpkin pie, all for $1.50 per person.

Thanksgiving in Tacoma as a Day of Work, Not Rest

People tried to keep Thanksgiving as normal as possible. Churches held special holiday services. Many attended the annual Stadium High School vs. Lincoln High School football game.

Others had to work. While stores, banks and government offices closed, war industries such as Tacoma’s bustling shipyards and iron foundries kept on schedule. Others volunteered at USO clubs across Tacoma to entertain soldiers far from home on the family holiday. People were encouraged to contact the USO if they wanted to host a soldier or two at their family’s Thanksgiving dinner. Because the day was business as usual at Fort Lewis and McChord Field, now JBLM, most could only get leave to come in the evening.

Other soldiers enjoyed events at the USOs across Tacoma, including dances and socials. Soldiers also held their own football games between units. In 1942, the Powder River “boys” clashed against the Caissons.

Victory and Peace

In 1945, people had a new reason to be thankful — peace had come. The war was over. Soldiers were coming home. “It has been so long since an editorialist could sit down and write the usual platitudes about our great and unique national holiday,” reflected a columnist in the Tacoma News Tribune a year later, “without feeling like a hypocrite.” But now, he concluded, the war was won. Loved ones were coming home. The future of America was looking bright.